Read The Manuscript authored by Arfang Madi Sillah.

By Arfang Madi Sillah, Washington DC

Chapter 1: A Marriage of Convenience

In the euphoria that followed Yahya Jammeh’s much-celebrated departure, the Gambian media found itself at a precarious crossroads, straddling the line between cautious optimism and profound skepticism. For decades, under the tyrannical fist of Jammeh’s regime, the press had been a battered and bruised entity—pushed to the margins, suffocated by censorship, and, at times, snuffed out with brutal precision. Jammeh didn’t just silence dissent; he obliterated it, as one might crush a mosquito—swift, ruthless, and with little regard for the consequences. But with Adama Barrow’s ascent to power, there was a collective sigh of relief across the newsrooms of Banjul and beyond. It seemed as though the long nightmare of press suppression had finally come to an end. Barrow, an unassuming political figure with the air of a man who had stumbled into power, promised democracy, reform, and, most tantalizingly, freedom for the press.

Even the late Pa Nderry Mbai, the most combative voice in Gambian journalism, couldn’t hide his elation. Mbai’s Freedom newspaper and radio station had, in many ways, led the charge that ultimately toppled one of the most brutal regimes in modern African history. For Mbai and his comrades in the media, Jammeh’s ousting was proof that no dictatorship, no matter how entrenched, could withstand the relentless pursuit of truth. His broadcasts, often from the diaspora, had stirred the pot enough to keep the fire of rebellion alight, and now he stood victorious—or so it seemed.

But as any Fleet Street editor will tell you, the glow of political victory often dims under the harsh light of reality. Barrow, who had ascended to power with promises of press freedom, soon revealed the same old tricks of the trade, dressed in new robes. The early days of Barrow’s administration were filled with carefully staged gestures, designed to lull the media into a sense of security. Smiles were exchanged, hands shaken, and an air of cooperation seemed to hang over the corridors of power. For a fleeting moment, the press thought it had finally found an ally in government—a meek leader who understood the value of a free media. But, as with all political theatre, the opening act was little more than a well-rehearsed ruse.

What followed was a deft exercise in manipulation, cloaked in such quiet subtlety that only the most perceptive observers could grasp its full extent. Barrow, eager to distance himself from the brutish tactics of his predecessor, did not come with clubs or guns. He came with a smile, handshakes, and offers of high office. The press, once a ferocious beast, was invited into the halls of power, where it would dine at the same table as the very politicians it had spent years scrutinizing. The first notable move came when Demba Ali Jawo, a veteran journalist whose pen had often skewered the Jammeh regime, was appointed Minister of Information. To many, this appointment seemed a signal that Barrow intended to uphold the values of transparency and press freedom. After all, what better way to prove one’s commitment to the Fourth Estate than by elevating one of its own to the corridors of power? But in hindsight, it was the first step in what would become a methodical campaign to neutralize the press.

Soon after, Ebrima Sillah, another respected journalist, was named Director General of GRTS, The Gambia’s state-owned broadcaster. His rise through the ranks was cemented when he too was promoted to Minister of Information, a position that placed him at the heart of Barrow’s communications apparatus. As the months wore on, other familiar faces from the world of journalism were also drawn into Barrow’s ever-expanding inner circle. Amie Bojang-Sissoho became Director of Press and Public Relations at the State House, while Dr. Ebrima Sankareh assumed the role of government spokesperson.

To the untrained eye, this parade of appointments appeared to be the ultimate endorsement of press freedom—a government that genuinely valued journalists. But for those with a nose for political theatre, the truth was much darker. By welcoming journalists into the fold, Barrow wasn’t empowering them; he was taming them. Much like the way Vladimir Putin turned Russian oligarchs into lapdogs by giving them a stake in his regime, Barrow had figured out that the best way to silence the press was not through brute force, but through co-option.

For the press, this was the beginning of a slow, steady decline. Once fierce critics of the state, journalists now found themselves in government, sipping tea in air-conditioned offices, far removed from the gritty realities of investigative reporting. The boundaries between the press and the state became so blurred that, for all intents and purposes, they no longer existed. It was reminiscent of what happened in Hungary under Viktor Orbán, where journalists were methodically absorbed into the state’s machinery until the once-robust press was reduced to a shadow of its former self.

The co-option didn’t stop at the upper echelons of the media. Lower-ranking journalists, who had once made names for themselves by exposing corruption and holding officials accountable, soon found themselves in cushy government jobs, often with salaries and perks far exceeding what they had earned in their newsrooms. Notable figures like Sanna Camara, Nfally Fadera, Lamin Njie, Bai Emil Touray, and Prince Baboucarr Aminata Sankanu, who had once been vocal advocates for press freedom, were now comfortably ensconced in the very structures of power they had once railed against. It was, in many ways, a marriage of convenience—journalists traded their pens for paychecks, their principles for prestige.

Given the considerable number of high-profile appointments of journalists into the ranks of Adama Barrow’s government, one might reasonably have anticipated a harmonious and productive relationship between the state and the media. One could even assume that such a marriage would foster coherent government policies, rooted in effective communication. However, in what can only be described as a most paradoxical turn of events, it appears that many, if not all, of the former journalists now embedded within government circles are proving to be even less capable than the politicians they once vociferously criticized. Their once-vocal critiques have been silenced, and in their place, we find nothing but obsequiousness, carried out with a fervor that would not seem out of place in a grand Greek tragedy. The longer these individuals remain ensconced in government, the more their shortcomings are laid bare for all to see. Not only is their ineptitude increasingly exposed, but their inability to tell truth to power actively undermines the government itself. Far from providing the constructive critique required to shape sound, solution-based public policies, these former journalists mislead the government, offering little more than sycophantic flattery. They have become complicit in perpetuating poor decisions, thus deepening the malaise of governance rather than offering the honest insights necessary to address it. From the perspective of anyone with even a modest education, it is clear that the majority of government communications—whether in the form of press releases or policy documents—are not only poorly composed but also marred by blatant plagiarism. This revelation begs the question: who had been writing these journalists’ articles when they were in the newsroom? Were these supposed top-notch journalists relying on ghostwriters all along, or did they owe their semblance of competence to the skillful hands of editors, who painstakingly transformed their crude drafts into publishable pieces?

As if originality were too much effort, Barrow appears to have taken the art of co-opting critics straight from the dusty archives of authoritarian survival kits. Rather than craft his own strategy, Barrow, ever the diligent apprentice, seems to have gazed across the border and thought, “Why reinvent the wheel when I can borrow it wholesale?” Barrow’s strategy of co-opting critical voices from the Gambian media closely mirrors that of his political mentor, former Senegalese President Macky Sall. In Senegal, Sall’s strategy to weaken the media was no less artful. The once-vibrant Senegalese press, hailed as a model of independence in West Africa, saw its brightest stars co-opted into the very halls of power they had once critiqued. Journalists like Abdou Latif Coulibaly, who had fearlessly exposed corruption in Senegalese politics, found themselves occupying high offices in Sall’s administration. Coulibaly, once a formidable critic of the state, became Secretary-General of the Government, his voice slowly fading into the cacophony of political sycophancy.

Then there was Suleiman Jules Diop, a heavyweight in Senegalese journalism, who transitioned from anchor desk to government communications advisor. It doesn’t stop there. Notable figures such as Yakham Mbaye, formerly the editor-in-chief of the influential Le Populaire, ascended to the role of Senegal’s Minister of Communication. Others, like El Hadji Hamidou Kassé, nestled into Macky Sall’s inner circle as strategic advisors, subtly transforming the media into little more than an extension of state power. The once-vibrant press, a staunch bastion of accountability, was gradually muted, its critical voices absorbed into the very machinery of government they once scrutinized. With each appointment, the lion’s teeth were pulled, leaving nothing but a docile creature incapable of dissent. This chilling trend was mirrored in the Gambian media under Barrow’s rule, where once fierce journalists were plied with government positions until they were no longer a threat. It was like watching a Shakespearean tragedy unfold, where the very critics of the regime became the architects of its propaganda.

However, this façade of harmony crumbled when Abdou Latif Coulibaly resigned as Secretary General of the Government on October 7, 2023. His resignation was a direct response to President Sall’s contentious decision to postpone the presidential election originally scheduled for February 25, 2024. This delay arose from a tumultuous clash between the National Assembly and the Constitutional Court over candidate eligibility, igniting a firestorm of institutional conflict that severely compromised the integrity of the electoral process. In stepping down, Coulibaly invoked a yearning for “full and complete freedom” to champion his political convictions, thereby illuminating the deepening fissures within Sall’s administration and the rising political tensions in Senegal. This rupture underscores a broader discontent within the political landscape, as critics decry Sall’s apparent subversion of democratic processes—an unsettling echo of Barrow’s own stratagems in The Gambia.

Barrow would do well to heed the cautionary tale of Sall’s experience: no amount of public relations finesse or media manipulation can ultimately salvage a corrupt and ineffective government. Just as Sall eventually faced the wrath of the Senegalese electorate, Barrow too will find that the Gambian people will not be fooled forever. His attempts to neutralize the press may grant him temporary refuge from scrutiny, but in the end, history is a relentless arbiter. The people will demand justice, and when they do, Barrow may find that the very press he thought he had tamed will be the first to turn on him, the very politicians he imagined were securely in his pocket will abandon him at the first whiff of danger, jumping ship with the kind of speed only opportunists can muster. The bureaucrats he relied on, those faithful servants of power, will resign en masse, turning their backs on him as though he had become a leper overnight. This isn’t conjecture—it has happened before, not only to Sall but to his predecessor Yahya Jammeh. In the eleventh hour of Jammeh’s reign, ministers, ambassadors, directors, and even his most sycophantic cronies scrambled for the exits, disavowing him with the fervor of born-again critics.

It was a spectacle in political treachery: those who had once sung Jammeh’s praises with nauseating zeal suddenly found their moral compass, resigning in droves and denouncing him as if they had only just discovered he was a dictator. The hypocrisy was palpable, as they postured as if they had been blind to his atrocities all along. Barrow is walking the same perilous path, and if he continues, he will find himself starring in this same tragicomedy. The very people he has surrounded himself with will, in the final act, turn from fawning courtiers to vengeful accusers, each eager to distance themselves from the impending wreckage. He will be left to face the cold reality that, in the world of politics, loyalty is as fleeting as the power that sustains it. And when the curtain falls, he will be left with nothing but the bitter irony of watching his carefully cultivated allies become his most fervent critics, their newfound moral clarity as hollow as their loyalty once was.

In a nutshell, the marriage of convenience between Barrow and the press is nothing new. It’s a tale as old as time, repeated throughout history by leaders who believe that by buying the silence of their critics, they can secure their place in power. But as every Fleet Street editor knows, you can’t muzzle the truth forever. The watchdog may have been coddled into submission for now, but there will come a day when it remembers how to bare its teeth. And when that day comes, Barrow will find himself very much alone, betrayed by the very journalists he once sought to control.

Chapter 2: The Fall of Mighty Tabloid

For 25 years, The Daily Observer stood resilient, weathering storms that would have sunk even the mightiest newspapers in places like imperial Russia, where the Tsarist regime shut down publications with brutal regularity, or in revolutionary France, where pamphleteers were imprisoned for daring to criticize the state. Much like those in the early days of Fleet Street or the clandestine newspapers of Weimar Germany, The Daily Observer fought on, publishing in an environment where the very act of reporting could invite retribution. Its pages, like the defiant underground presses of Franco’s Spain or apartheid-era South Africa, held within them the pulse of resistance, a truth too bold to be silenced. And yet, despite the constant threat of state retaliation, the paper persisted, standing as a symbol of defiance and a tribute to the resilience of the press.

For the journalists who worked at The Daily Observer, especially during the darkest years of Yahya Jammeh’s brutal dictatorship, the battle for free speech was not just a metaphor—it was a life-and-death struggle. Editors and reporters were not merely censored—they were pursued, arrested, tortured, and deported with the ruthless efficiency of a state determined to suppress every dissenting voice. Jammeh, much like Stalin’s NKVD or Pinochet’s secret police, led a crusade against the press, rounding up foreign journalists like the illustrious Sule Musa, deporting them as if they were dangerous revolutionaries. And when expelling foreign correspondents failed to quench his thirst for control, Jammeh turned his sights on Gambian-born journalists. Baba Galleh Jallow, a son of Farafenni and once the head boy at Gambia High School, narrowly escaped deportation after being mistaken for a foreigner in a farcical episode of state paranoia. It was the absurdity of despotism at its finest—where even your nationality could be questioned by the regime in its frenzy to control the narrative.

Inside The Observer’s newsroom, the atmosphere was charged with the tension of a war zone, where the simple act of reporting became a subversive strike against the iron fist of the state. Journalists operated under the constant threat of raids, arrests, and state-sponsored intimidation. Yet, like the muckrakers of early 20th-century America or the bold writers of samizdat publications in Soviet Russia, the journalists at The Daily Observer remained unbowed. They had seen the worst the regime could throw at them, from secret police interrogations to the shuttering of their offices. So, when Barrow’s administration took over, many seasoned reporters thought it was just another round of political theater—a new regime flexing its muscles. After all, they had outlasted Jammeh—what could Barrow’s government possibly do that they hadn’t already survived?

But Barrow’s tactics were subtler, less overt, but no less effective. This wasn’t the era of secret police and midnight knocks on the door. Instead, Barrow’s administration wielded the weapons of financial suffocation and bureaucratic strangulation with the precision of a seasoned autocrat. The assault wasn’t about arrests or disappearances—it was about tax bills, regulatory fines, and legal notices. What Jammeh couldn’t achieve through force, Barrow sought to accomplish through paperwork and financial ruin. Like the quietly insidious legal warfare waged by Nixon’s administration against the Washington Post during the Watergate scandal, Barrow’s government used bureaucracy to strangle The Observer out of existence without ever firing a shot.

For the battle-worn journalists, this was a new kind of war. It wasn’t fought in the streets or with megaphones—it was a war waged behind the closed doors of administrative offices, where ledgers and tax codes replaced handcuffs and riot police. So, what had started as a hopeful new dawn for democracy under Barrow quickly morphed into another chapter of press repression, this time cloaked in the polite language of fiscal responsibility and legalistic procedure. The fight for The Daily Observer was far from over, but the battlefield had changed, and the enemy now wore the face of bureaucratic efficiency rather than military dictatorship.

The fall of The Daily Observer was a watershed moment in Gambian media, marking a profound shift in the dynamics of the press. Founded in 1992 by the esteemed Liberian journalist Kenneth Best, the paper had long stood as a torchlight of fearless journalism, exposing corruption and speaking truth to power with the kind of boldness that only the truly independent can afford. But the tide began to turn in 1999 when Kenneth Best sold The Observer to Amadou Samba, a businessman firmly ensconced in Jammeh’s inner circle. Much like Hearst’s purchase of major newspapers in the early 20th century, this wasn’t merely a business deal—it was the beginning of the end for the paper’s editorial independence.

The shadow of Jammeh quickly spread over the once-independent Observer, transforming it from a vibrant, critical voice into little more than a mouthpiece for the regime. Journalists who had built their reputations on integrity and courage—people like Baba Galleh Jallow, Demba Ali Jawo, Alieu Badara Sowe and Pa Nderry Mbai—were swiftly dismissed in a purge that sent shockwaves through the media landscape. The newsroom that had once been a bastion of press freedom became a state-controlled megaphone, with every word scrutinized and sanitized by the regime’s ever-watchful eye. Like the great purges of critical voices in Weimar Germany, The Observer’s transformation was swift and devastating.

Despite its fall from grace, The Daily Observer remained a major player in Gambian media. But when Yahya Jammeh was finally ousted, the paper’s fate was sealed, much like a Greek tragedy where the hero’s downfall is sealed by the loss of divine favor. No longer shielded by the regime it had once supported, The Observer became vulnerable to the same tactics it had helped enforce. In June 2017, the Gambia Revenue Authority closed the paper’s doors, citing an unpaid tax bill of 17 million dalasis. But few believed the official story. Much like the closure of The Times under Margaret Thatcher’s government during the Wapping dispute, this was about power, not money. The demand for an immediate 30% settlement of the bill was financial warfare, designed to ensure the paper’s demise.

On June 14, 2017, The Daily Observer was shuttered, its offices sealed, and hundreds of employees left without jobs. The management’s offer to settle the debt over twenty years was rejected out of hand, a clear sign that the closure had nothing to do with taxes and everything to do with silencing a potential threat to the new political order. The tactics were new, but the outcome was the same—The Observer, once the titan of Gambian journalism, was no more.

What was perhaps most unsettling was the silence from the rest of the media. The Gambian Press Union issued a mild statement, but there was no collective outcry, no show of solidarity. Some media outlets even saw The Observer’s demise as an opportunity to expand their own influence—a short-sighted move that ignored the broader implications of the government’s actions. Like the fracturing of Fleet Street when The News of the World fell in scandal, the Gambian media failed to see that the fall of one paper weakened the entire ecosystem.

The ripple effect was immediate. Journalists across the country took note: if The Daily Observer could fall, none of them were safe. Self-censorship spread like wildfire, as media outlets already dependent on government advertising revenue grew even more cautious. Where once bold reporting had been the hallmark of Gambian journalism, caution and timidity now ruled the day. The closure of The Observer was a stark reminder that even in a post-Jammeh Gambia, press freedom was fragile, and the government’s grip on the media was far from loosened.

More troubling was how the paper was not only betrayed by its sister newspapers, but by its own sons and daughters—the journalists who once worked there, built their careers, and established their fortunes. These journalists, who owed much of their success to the crucible that was The Daily Observer, turned a blind eye and maintained tight lips as the mighty paper was brought to its knees. It was as if the closure of this media giant was an act of divine will, when in fact, it was the result of human neglect.

The closure of The Daily Observer wasn’t just the end of a newspaper—it was the beginning of a new era of media monopolization. Fewer outlets now controlled the narrative, and the diversity of thought that had once defined the press began to shrink. Other publications may have celebrated their increased market share, but they failed to see the bigger picture: the elimination of The Observer weakened the entire press landscape. The media became ripe for manipulation, as the remaining outlets faced the same financial and political pressures that had led to The Observer’s demise.

Long before the Gambian government even entertained the thought of establishing a school of journalism, The Daily Observer had already cemented its place as the veritable cathedral of Gambian journalism, functioning as a de facto academy for journalists. It wasn’t merely a newsroom—it was a classroom, shaping the next generation of journalists, writers, and scholars with hands-on experience and mentorship. The newsroom, helmed by seasoned editors who doubled as mentors, welcomed not only trained journalists but also aspiring writers—students with a passion for the written word. It was a sanctuary for the curious, the bold, and the restless—a place where the spark of inquiry was nurtured and transformed into the fire of journalism.

Young talents like Baboucarr Ann, Rohey Samba, Bamba Khan, Bankole Thompson, Sheriff Bojang Jr., and Simon Peter Mendy all started writing for The Observer while they were still in high school or middle school. And unlike today’s internship models, which often exploit young talent for free, The Observer paid its contributors handsomely, recognizing that good journalism deserves good compensation. The paper, like the great publications of Victorian England, understood that fostering talent was not only about opportunity but also about fairness.

This paper was the bedrock upon which many of today’s prominent media figures built their careers. Momodou Musa Touray, now the publisher of Gambiana; Sheriff Bojang, the publisher of The Standard; Assan Sallah, the publisher of LamToro News; and Bankole Thompson, the publisher of The PuLSE Institute, a Detroit-based, independent non-partisan think tank—all of them are products of The Daily Observer. Today, these men now hold the levers of power in Gambian and international media, continuing the tradition of journalism they honed at The Observer. Their rise to prominence in the media landscape speaks volumes about the training and opportunities The Observer provided to young journalists, offering them a platform from which they could grow into industry leaders.

Beyond the media realm, the impact of The Daily Observer has reverberated across many sectors of Gambian society. Countless former staffers of the paper are now making waves in a wide range of fields, from politics to academia, law, and public service. Take, for example, Yankuba Darboe, the current Chairman of the Brikama Area Council, whose time at The Observer sharpened his skills in public communication and administration. His rise in local government is a reflection of the far-reaching influence the paper had in shaping minds capable of leading and influencing communities.

In the legal field, we have Lawyer Alhagie Abdoulie Fatty, another former Observer journalist, who has carved out a significant presence in Gambian law, representing high-profile cases and advocating for justice. Fatty’s journey from the newsroom to the courtroom exemplifies how the skills of critical thinking, research, and analysis honed at The Observer can translate into effective legal advocacy and leadership. His transition from writing headlines to defending the downtrodden in courtrooms recalls the transformation of the ancient Greek orators—think Demosthenes—whose rhetorical prowess and commitment to justice influenced the course of history.

Academia, too, is home to Observer alumni. Dr. Ebrima Ceesay, now a respected professor at the University of Birmingham, is another product of the paper’s rigorous journalistic environment. His scholarly contributions and his work in educating the next generation of thinkers and leaders can be traced back to the foundations he built during his time at The Observer. His colleague, Dr. Baba Galleh Jallow, has also made his mark, contributing to the intellectual landscape both in The Gambia and abroad. Much like the ancient Athenian academies, The Observer was a modern-day Agora, where debates, ideas, and critical thought flourished.

One cannot help but draw parallels with Fleet Street in its heyday, when it wasn’t just a hub for journalism but a breeding ground for intellectuals, reformers, and future statesmen. Just as figures like Charles Dickens, who began as a Fleet Street journalist, went on to shape British literary and social thought, so too have the graduates of The Daily Observer moved beyond the confines of journalism to influence law, politics, and scholarship. The Observer’s newsroom was akin to a crucible of talent, where raw potential was refined into the very leaders shaping modern-day Gambia.

The list of distinguished alumni does not stop there. The Daily Observer nurtured a wealth of talent that has dispersed into various sectors, with former staffers contributing to business, education, and civil society. The paper was not just a media institution; it was a training ground for excellence, instilling in its staff a sense of responsibility, critical thinking, and a commitment to truth and service that transcended journalism. As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus once mused, “Character is destiny”—the Observer forged character in its staff, and their collective destinies now play out on national and international stages.

And yet, despite their successes, the closure of The Observer passed with little more than muted murmurs. These alumni of The Observer, many of whom now wield significant influence, could have banded together to rally for its survival, to challenge the government’s decision, or at least ensure the dignity of the paper’s closure. But there was no grand defense mounted, no significant effort to fight back.

To compound matters, while The Daily Observer was shuttered and its staff left unpaid, the government’s actions were cloaked in a veneer of legality. The argument was that the paper owed taxes—but the amount cited was not enough to justify the indefinite grounding of such a vital media institution. Activists such as Madi Jobarteh, who are now vocal about the ongoing standoff between President Barrow and The Voice, should be reminded that The Observer deserved no less of a defense than The Voice does today. In fact, The Observer deserved it more, as they were victims in a war not of their making, while some of The Voice’s troubles are self-inflicted.

The failure to defend The Observer was not just a failure of the media; it was a failure of Gambian society to stand up for one of its key institutions. The very paper that trained so many journalists, built so many careers, and became a voice for the people, was left to die, not because it deserved to, but because those who could have fought for it chose not to. It was a betrayal of the highest order, a reminder that in the cutthroat world of media, even the mightiest can fall if those they helped elevate turn their backs at the crucial moment.

In the final analysis, the closure of The Daily Observer was more than just a blow to the press—it was a blow to Gambian democracy itself. Without a free and independent press, corruption thrives, power goes unchecked, and the people are left voiceless in the face of injustice.

Then came a twist of irony so bitter that it left many shaking their heads. Not long after the closure of The Daily Observer, The Standard, one of the country’s leading newspapers, awarded its prestigious ‘Man of the Year’ title to the very figure whose institution had overseen the shutdown of The Daily Observer. This decision stunned the media community, as the award went to the head of the Gambia Revenue Authority (GRA), the very agency responsible for enforcing the closure. The Standard, in its celebratory piece, praised the awardee for his dedication to national development and commitment to fiscal responsibility. Nowhere in the glowing accolades was there any mention of the hundreds of jobs lost or the damage done to press freedom through the closure of the country’s largest newspaper.

For many, the decision to award such an honor to someone so closely linked to the suppression of The Daily Observer felt like a betrayal of journalistic principles. It was a stark reminder that the media was not immune to the same political and economic pressures that had long shaped other sectors. The award ceremony was held with pomp and circumstance, attended by the country’s political and business elite. Speeches were made, and toasts were raised, all while the ghost of The Daily Observer loomed large over the proceedings. The very institution that had silenced a major voice in Gambian journalism was being celebrated, while those left jobless and voiceless by the paper’s closure watched in stunned disbelief.

Simply put, The Standard newspaper’s baffling choice to crown Yankuba Darboe, the Commissioner General of the GRA, with the highest accolade a newspaper could offer, was the height of absurdity. Here was a man presiding over an organization that had become synonymous with corruption and bureaucratic buffoonery. What on earth were the criteria? Was it the efficiency of his spin machine or the depth of his advertising budget? How many dalasis did the GRA pour into The Standard’s coffers to secure this honor? The situation was eerily reminiscent of the practices described by David Simon in Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, where local politicians bought favorable coverage from cash-strapped newspapers. A similar case can be seen in post-Soviet Russia, where media moguls close to the Kremlin have been known to orchestrate awards and accolades to government officials in exchange for favorable coverage, thereby eroding the very principles of independent journalism.

The absurdity of the situation wasn’t lost on the public or the journalistic community. It revealed the widening gap between the ideals of the press and the reality of its operations in The Gambia. The awarding of a ‘Man of the Year’ title to someone so entangled with the destruction of The Daily Observer was not just an insult to the profession, but a sobering acknowledgment that even the press could be bought and sold, its moral compass thrown off course by political and financial expediency. This event left a deep stain on Gambian journalism, raising uncomfortable questions about the role of the media in a post-Jammeh Gambia, and whether it was truly free, or simply reshaped to serve a new set of masters. The case is reminiscent of Mexico’s Manuel Buendía case, where investigative journalists were killed or silenced, and the government honored figures of authority who played a role in the suppression of press freedom. Awards were used as tools to cleanse reputations, leaving the public disillusioned and the journalistic community demoralized.

Ultimately, this recognition by The Standard symbolized a disturbing normalization of state influence over the press. Rather than standing as an institution that held power to account, the media seemed increasingly complicit in bolstering those very forces that sought to silence it. It wasn’t just the closure of The Daily Observer that was troubling—it was the growing sense that the entire media landscape had become a mere extension of the same political machinery that once crushed dissent. This moment set a dangerous precedent, one in which the press, once the guardian of democracy, was slowly being turned into its own gravedigger. As seen in Turkey under President Erdoğan, where once-thriving independent media outlets were systematically shut down or co-opted into state-run propaganda machines, the parallels were stark. The Gambia now risks heading down the same path, where press freedom exists only in name, while the media quietly succumbs to political influence and economic pressures. The once-vibrant journalistic landscape is in peril, as the grip of power tightens around the throat of free expression.

Chapter 3: Echo Chambers of Power

In any thriving democracy, the press serves as an indispensable watchdog—a critical force capable of illuminating the darkest corners of governmental malfeasance and holding the powerful accountable. Journalists, armed with pen and paper—or today, digital devices—are expected to delve deep into the machinations of power, exposing corruption, injustice, and the various ailments that plague society. However, in The Gambia, this noble ideal has been laid to rest, smothered beneath the weight of complacency and co-optation. The media landscape has metamorphosed into a lamentable tableau where newspapers merely regurgitate sanitized narratives churned out by the government’s public relations machine or, worse, fabricate stories out of thin air, relying on phantom sources.

In fact, the last seven years have witnessed an alarming decline in serious investigative journalism in The Gambia, as many editors, reporters, and publishers continue to cash in by selling out instead of selling stories. When was the last time a Gambian minister felt the sweat of panic at the mere mention of their name in print? When was the last time a newspaper headline sent shivers down the spine of those occupying the corridors of power? The answer, regrettably, is that such moments have become relics of the past. Today, it is not the government trembling in fear of an investigative headline; it is the press itself that seems paralyzed, tiptoeing around the truth as if it owes its loyalty to those in power. The watchdog has become the handmaiden of the very system it was meant to keep in check. Ministers who once feared the wrath of the press now stroll confidently through the corridors of power, knowing full well that the media has been neutered. In other words, the roles have reversed—the government no longer shivers at the thought of the press; rather, the press seems terrified to poke the hornet’s nest of power, acting as though its survival depends on keeping those it should scrutinize firmly out of its crosshairs.

It is a well-established fact in political science that the media plays a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. What the public knows and believes is largely determined by what the press chooses to report—or, increasingly, what it chooses not to report. This is the essence of agenda-setting theory: the power to tell people not what to think, but what to think about. The role of the press in a democratic society is to serve as a platform for diverse viewpoints and to foster a robust exchange of ideas. Citizens should have free access to the press to exchange ideas, and views should be open to scrutiny because that is how civil society thrives. Yet, in their handling of public debate, mainstream Gambian publications such as The Standard, The Point, The Voice, and FOROYAA have effectively functioned as echo chambers, selectively amplifying the voices of certain individuals while systematically excluding alternative viewpoints.

This editorial censorship has stifled the plurality of voices that is the lifeblood of any vibrant journalistic landscape. It’s as though to appear in the local press, one must possess not just a sound argument but also a secret handshake and the approval of editorial overlords. Whether due to bias, favoritism, or a reluctance to disturb the carefully curated intellectual status quo, the result is a monopoly of ideas where only select voices are amplified. This creates an intellectual bubble that fosters a false sense of invincibility—an environment where critique is unwelcome and dissenting voices are systematically excluded. We’ve seen similar issues in Britain, where The Guardian has been accused of promoting certain political narratives while sidelining others. Gambian media seems to be following this path, trading intellectual diversity for a comfortable but stagnant intellectual environment.

For years, local newspapers have published the musings of self-proclaimed intellectuals, shielding them from the kind of rigorous scrutiny that is essential for the growth of ideas. Any attempt to offer well-reasoned rejoinders aimed at dismantling these flawed narratives has been conveniently sidelined, never seeing the light of day. This practice mirrors what George Orwell warned against in Animal Farm: a media environment where certain voices are “more equal than others.” It’s not just about bias; it’s about the erosion of a marketplace of ideas, leaving readers to accept a narrow and unchallenged narrative. By shutting down robust debate and limiting the scope of intellectual engagement, the media has betrayed its duty to the public. They’ve turned the media landscape into a curated platform for the few, leaving readers clutching at straws for a shred of genuine journalism.

This is where the shadow of Dr. Assan Jallow looms large. His long-winded, often incoherent ramblings are given pride of place in the very newspapers that should be holding his ideas to account. It’s not that his ideas are particularly bad; it’s that they’re seldom, if ever, challenged. His recent articles on Dr. Mamadou Tangara were initially published in The Standard, which, as a responsible outlet, should have been the first to offer space for a right of reply to anyone wishing to counter his arguments. Yet, for some reason, The Standard appears reluctant to publish any counterarguments, almost as if they are shielding these mediocre intellectuals behind some form of editorial protection—akin to paying a kind of “intellectual protection fee.” In this, the state of Gambian journalism is reminiscent of the darker days of British tabloid journalism, where the likes of Richard Desmond, with his scandal-plagued tenure at the Daily Express, turned the media into a playground for the well-heeled and well-connected. The entire affair reeks of a pay-for-play racket, a betrayal of journalistic principles where coverage can be bought, and editorial stances are up for sale. How can they call themselves independent when they’re more concerned with playing favorites than with serving the public good? This transformation of journalism into a commodity is exactly what Evelyn Waugh satirized in Scoop, a novel that mocks the absurdities of a press more interested in selling than serving. The Gambian media seems to have embraced Waugh’s satire as a playbook, turning their pages into marketplaces where truth is negotiable.

Dr. Assan Jallow and many of the so-called Gambian intellectuals are prime products of this environment. Scholars who have grown accustomed to having their work published unchallenged are insulated from the peer review process that would otherwise expose the glaring flaws in their reasoning. In scenarios where these so-called scholars, like Dr. Jallow, make glaring errors or espouse questionable arguments, the mainstream media’s lack of accountability mechanisms ensures that such mistakes go uncorrected, further entrenching the misconception that their work is beyond reproach. In the past, individuals like Dr. Jallow were able to bask in the glow of unearned intellectual reverence—not because their ideas were particularly insightful, but because the opportunity to critique and challenge their work was systematically denied. Their voices dominated the public sphere simply because opposing voices were silenced by editors who appeared intent on maintaining an intellectual hierarchy where only a select few enjoyed the privilege of being unassailable. This created a stagnant intellectual landscape where critique was not only discouraged but actively suppressed, resulting in a one-sided discourse devoid of the dynamism and vibrancy that true debate brings.

Evidently, there is an underlying “pay-to-play” dynamic at work, where financial incentives, rather than the merit of ideas, often determine who gets published. This has created an intellectual marketplace where visibility and influence are not earned through rigorous scholarship but purchased through economic means. Such practices undermine the credibility of these media outlets and contribute to the proliferation of unchallenged, substandard intellectual content.

But all is not lost. The growth of independent online platforms is beginning to crack the foundation of this journalistic charade. These digital Davids, armed with laptops and a desire for truth, are challenging the Goliath of mainstream complacency. They’re doing what the traditional press has failed to do—holding the powerful to account, giving voice to the voiceless, and daring to tell the stories that others are too timid to touch. They’re the digital pamphleteers of our time, carrying on the legacy of Thomas Paine, who knew that “the pen is mightier than the sword” only when it’s not sold to the highest bidder.

These digital outlets, dedicated to promoting open debate and diverse perspectives, are exposing the shortcomings of established figures like Dr. Jallow. For the first time, Gambian readers are being presented with a more balanced intellectual landscape, where alternative viewpoints are not only heard but also critically engaged with. This shift is gradually dismantling the illusion of intellectual authority that individuals like Dr. Jallow have long enjoyed, subjecting their ideas to the rigorous scrutiny they have previously evaded.

This emerging trend is reflective of the grand tradition of intellectual inquiry that has shaped human thought from Classical Greece to the Enlightenment era. From the days of Classical Greece, intellectuals like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle championed the value of debate, reason, and—most importantly—the scrutiny of ideas through peer review. It was their firm belief that truth could only be uncovered through rigorous examination and dialogue, where no thought was considered too sacred or inviolable to be questioned. Socrates, with his relentless dialectical method, engaged his interlocutors in a quest for clearer understanding, always urging them toward greater intellectual humility. Plato’s Republic epitomizes this process, presenting competing arguments that expand the boundaries of knowledge through rigorous debate. Aristotle, not to be outdone, established the Lyceum, where intellectual exchange was not a monologue but a sophisticated dialectic—one that sharpened the minds of all who participated.

Fast-forward to the Enlightenment, and we see philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Kant carrying forth the torch of reason, championing free debate not to destroy the views of others, but to refine and develop one’s own ideas through robust critique. Rousseau’s quarrels with his contemporaries over the nature of human society and Voltaire’s relentless advocacy for free speech were rooted in the conviction that only through contestation could truth be pursued. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is an enduring testament to the value of challenging and interrogating received wisdom. The method of peer review—inviting scrutiny to ensure no argument stands untested—has been the linchpin of intellectual progress for centuries. It is this spirit of rigorous inquiry that sustains the advancement of human thought.

The emergence of independent media in The Gambia is thus a return to these fundamental principles of intellectual engagement. By breaking the monopoly of mainstream outlets and allowing a plurality of voices to be heard, these new platforms are reviving the classical tradition of open debate and critical inquiry. They are ensuring that no idea remains beyond scrutiny and that the truth, however inconvenient, is pursued through rigorous examination. In this new environment, figures like Dr. Jallow can no longer rely on unchallenged platforms to uphold their intellectual stature; they must now engage with their critics and refine their ideas through the very process that has historically propelled human knowledge forward.

The democratization of information through online media has leveled the playing field, making it increasingly difficult for mainstream outlets to continue their exclusionary practices. In this revitalized intellectual landscape, all ideas—regardless of their source—must withstand public critique and debate. As a result, the Gambian intellectual community is beginning to break free from the constraints of media gatekeeping, paving the way for a more vibrant and dynamic exchange of ideas that honors the timeless tradition of inquiry from Classical Greece to the Enlightenment.

So, let’s not kid ourselves. The mainstream media in The Gambia isn’t about serving the public good; it’s about serving its own interests, peddling influence while pretending to champion the common man. The real heroes are those in the new media, those who dare to challenge the narratives, who refuse to be bought off or intimidated. And it’s high time the Gambian public stood behind them, because the true battle isn’t between Barrow and the media—it’s between a press that serves itself and a press that serves the people. While the challenges are substantial, the emergence of a more diverse and independent media landscape offers hope that The Gambia can move beyond the dark days of information control and towards a future where the press genuinely serves the public interest.

Chapter 4: Journalism vs Churnalism

In today’s fast-paced media environment, the pursuit of profit has overtaken the pursuit of truth. Journalism, once seen as a noble endeavor to inform, educate and entertain, has increasingly been reduced to “churnalism”—a term popularized by Nick Davies to describe the practice of recycling press releases and superficial content in place of original investigative reporting. This process has transformed news into a commodity, driven not by the need to hold power accountable but by the need to attract clicks, advertisers, and revenue streams.

The rise of “churnalism” has become a defining feature of the Gambian press under President Adama Barrow’s dispensation. Under pressure to produce content quickly and frequently, journalists have increasingly relied on ready-made stories provided by government agencies, NGOs, and corporate entities. This trend reflects a broader global pattern where newsrooms have reduced their investigative capacity, focusing instead on quantity over quality.

The role of the reporter, once seen as the frontline investigator who holds power accountable, has been relegated to that of a conveyor of pre-packaged information. Editors, who should act as gatekeepers ensuring the accuracy and integrity of stories, now face immense pressures from advertisers and publishers to prioritize profits over hard-hitting journalism. As a result, the symbiotic relationship between the press and the public has weakened, with the public left with little more than sanitized content that skirts around real issues.

At its core, newspapers are meant to serve the public by providing timely, accurate information on local, national, and international events, keeping citizens informed on critical issues such as politics, economics, and culture. This function helps the public stay engaged with the world around them, reinforcing democracy through a well-informed electorate. Newspapers serve as a key institution in any functioning democracy, bridging the gap between those in power and the people. Advertisers, however, often exert significant influence, leading to self-censorship and the dilution of investigative journalism that could upset commercial relationships. Publishers, concerned with circulation numbers and revenue, sometimes push editors to favor sensationalist or trivial stories over in-depth reporting. As Walter Lippmann emphasized in his seminal work Public Opinion (1922), the media plays a pivotal role in shaping public perceptions and discourse, yet the editorial independence necessary to fulfill this role has increasingly been compromised.

A fundamental role of the press is to act as a watchdog, uncovering corruption, abuse of power, and societal injustices through investigative journalism. Globally, the press has often been a cornerstone in holding governments accountable. The famous investigative work of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein during the Watergate scandal, for example, proved how essential journalism can be in protecting democracy (All the President’s Men, 1974). In The Gambia, however, investigative journalism has almost entirely disappeared, reflecting a disturbing retreat from the press’s most essential function. The editorial hierarchy—starting from reporters and passing through sub-editors and senior editors—has become more inclined to pursue safe, uncontroversial stories that align with the interests of powerful stakeholders. This systemic failure is compounded by owners and publishers who prioritize maintaining political and corporate alliances over championing journalistic integrity. As such, instead of exposing wrongdoings, the media has allowed itself to be co-opted by the very systems it should be scrutinizing.

Another crucial function of the press is to educate the public. Through thoughtful, well-researched analysis, newspapers should provide readers with the historical and social context necessary to understand major events. John Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946), for example, is a hallmark of how journalism can enlighten the public on global issues. Yet in The Gambia, newspapers often fail to provide this level of depth, opting instead for surface-level reporting devoid of the necessary background or critical examination. The educational role of the press is especially important in a developing democracy like The Gambia, where access to balanced, informative reporting is vital for civic engagement. Editors, who should guide the narrative and shape public understanding, now prioritize clickbait or sensationalism over well-rounded analysis. Advertisers, too, exert undue influence by dictating what stories are told, further eroding the press’s educational mandate.

Newspapers also traditionally serve as platforms for public notices, legal announcements, obituaries, and classifieds. While often overlooked, these sections provide vital community information. Nick Davies, in his book Flat Earth News (2008), emphasizes the importance of local news in fostering community engagement. However, the growing commodification of news has diluted the press’s focus on community-centric reporting, sidelining crucial public service announcements in favor of sensationalism. This shift has left a vacuum in the media’s role as a bridge between the government and the public, particularly in local affairs. Editors, once the curators of balanced content, have increasingly deferred to commercial interests, sidelining the more mundane but vital aspects of community reporting. Publishers and advertisers, seeking higher profits, often push for content that draws more immediate attention, ignoring the essential civic role that newspapers should play.

Perhaps most disheartening is the erosion of the press’s role in facilitating public discourse. Newspapers are meant to provide a platform for debate and the free exchange of ideas through editorials, opinion columns, and letters to the editor. By presenting diverse viewpoints, they contribute to a more informed citizenry. The editorial sections, which should be the battleground for competing ideas, have increasingly become echo chambers, reflecting only the perspectives of those who hold power. In The Gambia, political polarization has infiltrated newsrooms, where dissenting opinions are either watered down or silenced altogether. This failure stems from a reluctance among editors and publishers to challenge the status quo or risk alienating politically powerful figures. In allowing this to happen, the press has compromised its responsibility to nurture a robust democratic debate, thereby leaving the public without a meaningful forum for civic engagement.

Collectively, these failures demonstrate how the Gambian press has not only lost its way but has contributed to its own decline. Instead of serving as fearless watchdogs of democracy, newspapers have become entangled with the very systems of power they are supposed to hold accountable. This entanglement has compromised editorial independence, leading to a media landscape where truth and integrity take a backseat to financial and political interests. Reporters are now beholden to editors who, in turn, are guided by advertisers and publishers focused on profit rather than journalistic standards. Without a concerted effort to reclaim journalistic integrity and independence, the media will continue to spiral downward, leaving the Gambian public misinformed and disenfranchised. A vibrant, free press is vital for any democratic society, but in The Gambia, the press seems more interested in protecting its interests than serving the people.

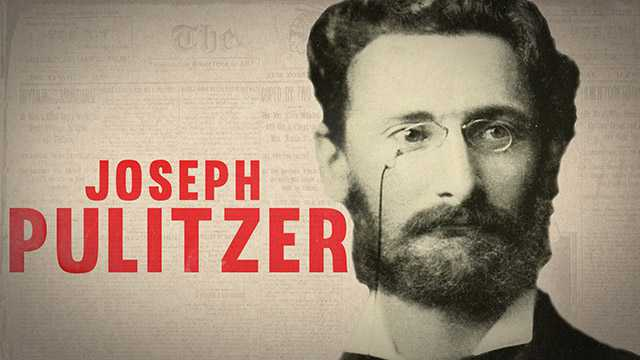

The legacy of Joseph Pulitzer offers a poignant contrast to the current state of journalism in The Gambia. Pulitzer, the Hungarian-born journalist who revolutionized American journalism, believed that newspapers should not only inform the public but serve as instruments of social change and accountability. His creation of The New York World exemplified his vision, using bold headlines and fearless exposés to capture public attention while promoting truth and justice. Pulitzer’s newsroom was guided by strict editorial standards, ensuring that every story, regardless of its potential commercial appeal, was accurate and impactful. His emphasis on “Accuracy!” became the bedrock of responsible journalism, reminding us that the ultimate duty of the press is to serve the public interest. His approach laid the foundation for what we now know as the modern press, for better or worse. In The Gambia, however, this guiding principle has been replaced by a profit-driven agenda, where editorial decisions are dictated more by advertisers and publishers than by a commitment to truth and accountability.

Chapter 5: Government Handouts

To be a journalist, one must not only be committed to uncovering the truth but also be willing to endure the hardships that often accompany such a vocation. True journalism is not a profession of luxury; it is one of sacrifice. A genuine journalist is undistracted by the allure of wealth and immune to the temptations of power, as their dedication lies with a higher purpose—the pursuit of an unvarnished truth. The calling requires a deliberate resistance to the shine of material comforts, to resist being seduced by incentives that might compromise one’s values. For a journalist with integrity, the truth cannot be bartered for financial security or fleeting prestige. Instead, they must be willing to stand firm in their principles, even if it means forgoing the conveniences and comforts that others readily chase. The true journalist embraces the challenges, remains steadfast in their commitment to the public interest, and resolutely refuses to let their voice be bought or silenced by those in power.

However, the ideals of journalistic integrity have been severely undermined in The Gambia since the regime change of 2017. Financial incentives, government handouts, and secret dealings have gradually ensnared Gambian journalists, eroding the independence of the press and turning it into a tool of power rather than a check on authority.

With the new administration came the subtle yet insidious practice of financial dependency. Media outlets that had struggled during the dictatorship now saw an opportunity for stability through government support. Initially, this seemed like a much-needed relief—an opportunity to rebuild, to strengthen, and to thrive in a new democratic era. Yet, this financial lifeline soon turned into a shackle. Handouts were given, not as benevolent gestures, but as a means to ensure compliance. Editorial independence was traded for financial security, and criticism of the government became less frequent, less pointed, and eventually, almost absent. The watchdog had been tamed, and its bark softened to a whimper.

This compromise was not confined to overt transactions; it also manifested in more covert ways. Media executives began to court the President himself, seeking financial incentives in exchange for favorable coverage. This was not journalism—it was public relations. What should have been a profession marked by a rigorous pursuit of truth was reduced to one of transaction and self-preservation. The moment these media leaders decided to approach the government for funding, they crossed a line that undermined the core values of their profession. The line between journalism and state propaganda became blurred, with the press willingly echoing the government’s narratives in exchange for financial stability.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought these dynamics into even sharper focus. As the pandemic wreaked havoc on economies, the Gambian media—already weakened and financially vulnerable—scrambled for government relief funds. Journalists, once tasked with holding power to account, found themselves lining up for government support, and with that support came expectations. The acceptance of government handouts during the COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in the media’s fiscal and operational independence. From an economic standpoint, this can be understood through the lens of rent-seeking behavior, where media companies, instead of innovating or cutting operational inefficiencies, sought to extract rents from the state. This dependency on state funds creates a perverse incentive structure, in which media outlets become beholden to the government, reducing their incentive to engage in investigative journalism or hold political elites to account. In journalistic terms, this compromises editorial independence, as economic pressures lead to the softening of criticism and the pursuit of more ‘palatable’ content for state actors. Rent-seeking, in this context, undermines the competitive spirit of journalism, leading to homogenization of content that aligns with state narratives. The failure to diversify revenue sources means that the media’s sustainability is at constant risk, and their editorial lines may be more aligned with preserving access to state resources rather than upholding journalistic principles. This economic and moral dependency further erodes public confidence, as consumers begin to see the press as no longer independent but as state-aligned, compromising its role as the protector of the public interest.

Perhaps the most egregious example of this compromise came with the secret distribution of forty million dalasis to select media outlets, purportedly to combat disinformation. This funding, under the guise of noble intent, was in fact an instrument of control. It was distributed to those media houses that had proven themselves compliant, those that were willing to align their editorial stance with the government’s interests. It was not about strengthening the media but about ensuring its loyalty. This selective support fostered a media cartel, where a few privileged voices dominated public discourse, while independent and critical outlets were systematically excluded from these financial benefits. The diversity of thought that is essential to a healthy democracy was stifled, replaced by a chorus of compliance.

Fatou Touray, CEO of Kerr Fatou, has publicly lamented that her media outfit was denied government advertising funds, specifically because it was viewed as being too critical of the Barrow administration and perceived as pro-United Democratic Party (UDP). Touray has highlighted how Kerr Fatou and other independent media houses have been deliberately excluded from lucrative government advertising opportunities, which are instead reserved for media outlets that align closely with government narratives. She pointed out that the state’s refusal to advertise with her media outlet was a deliberate attempt to stifle dissent and control the flow of information. This exclusion, she argued, is part of a larger effort by the Barrow administration to marginalize critical voices and ensure that state resources only benefit media organizations willing to provide favorable coverage. Such actions effectively punish independent journalism, pushing critical media to the fringes while rewarding loyalty to the government.

This blacklisting was allegedly enforced through covert directives to State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), instructing them not to place advertisements with Kerr Fatou. These directives were reportedly conveyed through informal channels, without official records, which added to the opacity of the process. Touray expressed deep disappointment in the president’s rhetoric and actions, describing them as a threat to press freedom. She argued that the government’s stance toward Kerr Fatou was an attempt to intimidate independent media into silence and compliance.

Touray’s claims hold more than a grain of truth, as similar transformations can be observed within other Gambian media outlets. Notably, there is an example of a news network that, before gaining access to government funding, was among the staunchest critics of President Barrow’s administration. However, within a few short years, once this outlet had secured government support and access to resources, its editorial tone shifted dramatically. What was once a relentless stream of criticism turned into effusive praise, almost as if orchestrated by an unseen hand.

This particular media outlet, once renowned for its critical stance against the Barrow administration, underwent one of the most striking reversals in the history of Gambian journalism. The transformation was as sudden as it was conspicuous: a former critic had now become one of the president’s most ardent supporters. Coverage that used to question every move of the administration was replaced with sycophantic reporting, lauding the president’s actions with an enthusiasm that seemed almost unnatural. It was as if the outlet had willingly traded its credibility for a comfortable relationship with those in power.

One cannot help but wonder whether there were clandestine negotiations, covert agreements, or perhaps even the exchange of ‘brown envelopes’ behind closed doors. While such speculations remain in the realm of conjecture, the shift was unmistakable. What had once been independent, fearless journalism transformed into adulation that verged on state-sponsored propaganda. The abruptness of this transition was further evidenced by the sight of the proprietress of this particular news network now socializing with members of the First Family—photographed with beaming smiles at events more reminiscent of state pageantry than independent journalism.

Advertising revenue, which could have been a means for these outlets to maintain independence, also became a mechanism of control. Lucrative government contracts were awarded to media houses that toed the official line, while those who dared to remain critical were denied access to such funding. This financial stranglehold ensured that those media outlets willing to serve as government mouthpieces prospered, while those who sought to maintain journalistic integrity struggled. The press, which should serve as a check on power, was instead participating in the very systems of patronage it should have been exposing.

The Gambia Press Union (GPU), which ought to be a paragon of journalistic ethics, failed to address these growing compromises. It allowed media houses to engage in these unethical practices without consequence, leading to the normalization of financial dependency and the degradation of journalistic standards. The lack of accountability from the GPU meant that compromised journalism became the new norm, eroding public trust in the media. The press, once viewed as an independent force, now appeared to be little more than a pawn in the broader game of political maneuvering.

The consequences of these compromises are far-reaching. Without an independent press, the mechanisms of accountability that underpin democracy are weakened. The Gambian people are left without a reliable source of information, without a media that represents their interests or questions those in power. The press, once a pillar of Gambian democracy, has become a tool for the government—a means to control the narrative and maintain power without scrutiny.

If the Gambian press is to regain its role as an independent force capable of holding power accountable, a fundamental change is needed. Media houses must break free from financial dependencies on the government, diversify their revenue sources, and reassert their editorial independence. The GPU must take an active role in ensuring that journalistic standards are upheld and that those who compromise the integrity of the press are held accountable. Only through such reforms can the press hope to reclaim its place as a cornerstone of democracy, serving the public interest rather than the interests of those in power.

The questions surrounding the GPU’s issuance of press cards to its members raise significant concerns about journalistic integrity and standards in The Gambia. How can the GPU, in good conscience, provide accreditation to individuals who seem to play both sides—functioning as journalists while simultaneously acting as PR representatives for the government or private interests? This dual role clearly compromises the essential independence that should define journalistic practice. The integrity of journalism is threatened when the boundaries between independent reporting and promotional activities become blurred.

It appears that the GPU has never penalized any journalist or media executive for professional misconduct throughout its history. This absence of accountability suggests that the Union is not enforcing the standards that are meant to safeguard the credibility of journalism. There are journalists whose actions have clearly crossed ethical lines, yet they continue to operate without facing any consequences. In other countries, professional misconduct in journalism, such as accepting bribes for favorable coverage or spreading misinformation, would lead to serious repercussions, including expulsion from the press union or revocation of accreditation.

If the GPU is to uphold its credibility and maintain public trust in Gambian journalism, it must take a firmer stance on journalistic ethics. The Union should not only review how accreditations are granted but also establish clear accountability mechanisms to address misconduct. Such measures are essential for the development of a truly independent press that serves the public rather than private or political interests. Without these reforms, the credibility of the GPU and the integrity of the Gambian media will continue to be questioned.

Chapter 6: The State House Visit

Not long ago, under the velvet skies of an April morning that seemed to shimmer with promise, the State House doors swung wide open to welcome a delegation of the Newspaper Publishers Association (NEPA). It was a scene that could have been pulled from the pages of ancient Greek lore, where grand halls held court to kings and philosophers, and the air itself seemed to hum with the weight of momentous things. The atmosphere, electric yet serene, draped itself over the gathering like a fine silk cloak. There were smiles, shared glances, and laughter, as if the gods themselves had blessed the moment with a rare ease. Cameras flashed, and conversation danced on the breeze like a melody long forgotten.

One might have thought, for a fleeting moment, that they were witnessing something out of time—those moments in faraway kingdoms when queens knight their loyal subject or when Santa Claus himself might have strolled into the State House, not on Christmas Eve but on a winter’s night of dreams. The newspaper executives, in turn, approached the President for photographs, not unlike pilgrims seeking a blessing. One by one, they took their turn, grinning for the cameras as though they had just met a living deity. There was something almost childlike in the ritual, as if the weight of their world could be lifted with a mere touch of the presidential hand.

But beneath the mirth, beneath the feasting and the festivity, a quieter, more somber note lingered in the shadows. The morning’s heart lay not in the pictures or the plates but in the hushed conversation that followed, where the talk turned to survival—of newspapers, of livelihoods, of voices. In a world tilting ever closer to economic collapse, how could the press, already on the brink, be saved? And so, the words ‘subvention’ and ‘government advertisement’ were passed around the room, bright as coins, glimmering with the promise of salvation. Yes, they went cap in hand, whining about subventions and government ads like a bunch of penny-counting bureaucrats.

Yet, as with all things too hastily sought, there was something missing. For while the press chiefs spoke of money, of the tangible burdens of their industry, they left unspoken the far greater menace—the ancient, rusted chains of press laws that had, for generations, hung heavy on the necks of journalists. Laws that stifled, laws that silenced. And in their eagerness to court the favor of the state, they forgot that it was not just their coffers that needed freeing, but their very souls.

Now, as the echoes of that fateful morning fade, the consequences have come rushing back like a tide. The arrest and detention of The Voice editor and reporter have awakened cries from the same press leaders who once dined in complacency. But these cries now ring hollow—too late, too empty, like the last song of a bird whose wings have been clipped by its own hand. Hypocrisy and regret twine together, the two-headed serpent of missed opportunity.

And so, the scene unfolds, not as a grand banquet but as a fable, where those entrusted with freedom’s torch allowed it to dim in exchange for the fleeting glow of favor. Though after the visit, the local press reported that NEPA had a productive meeting with the president, but besides the photo opportunity, what else was achieved? The media chiefs were so dazzled by the opportunity to rub shoulders with power that they completely forgot about the journalists they claim to represent. Their giddy excitement was palpable, like kids on a school trip to the State House—so much so that they couldn’t be bothered to challenge the very laws that have been weaponized against their colleagues.

Simply put, the recent statement by the NEPA calling on the police to drop charges against journalists Musa Sheriff and Momodou Justice Darboe presents itself as a disingenuous attempt to appear concerned about press freedom in The Gambia. Yet, one cannot ignore the glaring contradiction in their actions. When given the opportunity to meet with the president, instead of championing the repeal of draconian laws that threaten the freedom of expression, NEPA chose to prioritize their own financial interests—discussing government subventions and advertising revenue, as if these were the most pressing issues.

Sure, Sam Sarr of FOROYAA made a token nod to the need for reform, specifically calling for the repeal of oppressive laws such as criminal defamation and sedition. However, this was buried in a footnote, like an unwanted line item in a budget report. After the meeting, there was a conspicuous lack of tangible follow-up—no attempts to hold the government’s feet to the fire to ensure the president delivered on his promises. As Sam Sarr himself mentioned, the media cannot thrive on the ephemeral goodwill of leaders; they need these lofty words codified into law to offer genuine protection. How utterly naïve these press chiefs must be to believe anything the president proclaims about safeguarding journalists and promoting freedom! If he were genuinely committed, would he have dared to shutter The Daily Observer? This same president, who has backpedaled on his promises like a dancer trying to avoid a misstep, reneged on his vow to serve just three years before extending his term to five—and now he’s eyeing a third! This man is not merely a politician; he’s a master of the grand illusion, a conjurer of broken promises wrapped in velvet rhetoric.

If Musa Sheriff had known that just months after posing for those photo ops with the president, he would find himself in court battling for his freedom, perhaps he would have prioritized discussions about repealing those draconian laws over chasing advertising money. And let’s not forget Pap Saine, the managing editor of Point Newspaper, who, in a display of misplaced optimism, praised Barrow during the meeting for his alleged commitment to press freedom. He must be ready to eat his words now, given the latest lawsuit against The Voice and the relentless harassment from the police. The arrests, detention, and charges against journalists are now telling signs of a police state. If journalists cannot see this unfolding reality, bless their hearts.

It is both baffling and deeply ironic that NEPA would now place its faith in the very same Media Commission that one of its own, Deyda Hydara, stood vehemently against. On 14 December 2004, two days before his assassination, Hydara penned what would become his final article, a defiant call to challenge the Media Commission Act. He recognized the act for what it was—a weapon aimed at silencing dissent and tightening the government’s control over the press. The act’s provisions were draconian: harsher criminal penalties for defamation, exorbitant security bonds required to establish a newspaper, and the forced registration of journalists with a board, all under the guise of maintaining ‘professionalism.’

Hydara’s resistance was not just about protecting his livelihood; it was about safeguarding the freedom of the press and the public’s right to receive independent, uncensored information. For him, the Media Commission symbolized an existential threat to journalism in The Gambia. His assassination only underscored the high stakes involved in challenging such a law.

And yet, fast forward to today, NEPA appears to have abandoned Hydara’s cause, seemingly unperturbed by the Commission’s inherent dangers. This shift in position raises serious questions: Why is NEPA now aligning with a structure that Hydara viewed as a death knell for press freedom? Has the lure of government advertisements and financial stability clouded their judgment? It seems that, in its pursuit of survival, NEPA has conveniently forgotten the very principles that once defined the organization and its members. Hydara’s legacy, once a symbol of journalistic courage, now stands in stark contrast to NEPA’s acquiescence to a system he died opposing.

The fact that the Commission is headed by Neneh Macdouall-Gaye nullifies the entire premise of subscribing to such a body. Her tenure as Minister of Information during Yahya Jammeh’s regime—a period synonymous with the suppression of press freedom—casts a dark cloud over her leadership in this capacity. Gambian journalists who lived through the suffocating media restrictions of that era have every reason to question her suitability to oversee a body purportedly tasked with protecting the same freedoms she once undermined. But it seems that the local media chiefs suffer from selective amnesia, conveniently forgetting Macdouall-Gaye’s role in a regime that silenced dissent. Their high tolerance for government interference and short memories of past oppression make one wonder whether the principles of press freedom have been traded for political convenience or financial gain.

This brings us to the absurdity of having both the GPU and NEPA. Two organizations, same industry, but what exactly is NEPA doing that GPU couldn’t? By existing separately, they weaken the press as a whole. NEPA’s contentment with this split shows that unity isn’t the priority—it’s self-preservation. How convenient that when it comes to media regulation and financial perks, NEPA is always first in line to protect its own interests, but when it’s time to tackle the real issues—like the laws that stifle free speech—they’re nowhere to be found.

In the end, NEPA’s statement is nothing more than a feeble attempt to salvage their tattered reputation. They’ve squandered every opportunity to fight for press freedom, choosing instead to play nice with the powers that be. Now that the wolves are at the door, they’re screaming for mercy. But don’t be fooled. This isn’t about protecting press freedom. It’s about protecting their own interests, and they’ve shown they’ll sell out press freedom the moment there’s money on the table.