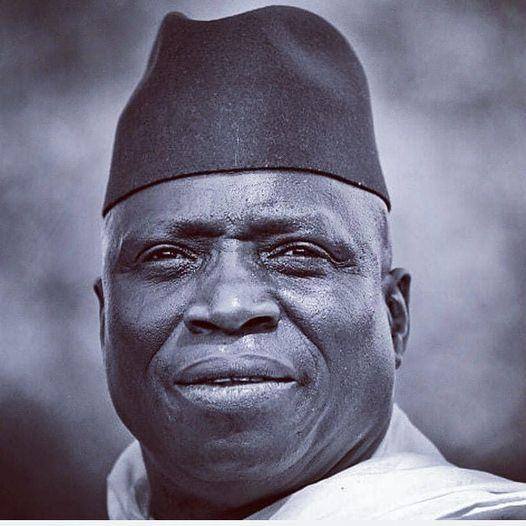

As a citizen of the Gambia, former President Yahya Jammeh possesses the constitutional right to voice his opinions. Nevertheless, given his status as an ex-head of state, it would be prudent for him to refrain from participating in active politics and instead concentrate on resolving his legal issues before an international tribunal, pertaining to the crimes against humanity committed during his twenty-two-year tenure of malevolent governance.

Fatoumatta: After reading former President Yahya Jammeh’s interview with The Atlantic, I am preparing a comprehensive response to his public statement to the people of Gambia. Yahya Jammeh’s continued interest in political matters is to be expected from a former head of state. However, it’s important to respect his constitutional right to free speech while recognizing that his active participation in politics ought to be restrained. He should confront the significant legal issues he encounters, including the human rights abuse allegations from his twenty-two years in office. Following his displacement from power, it would be wise for Yahya Jammeh to withdraw from political activities and concentrate on the legal accusations he faces, such as charges of crimes against humanity, torture, extrajudicial executions, and rape in an international tribunal. Additionally, he should focus on his family, philanthropic activities, agriculture, or other personal interests.

Active engagement in politics after retiring from the presidency might be seen as improper and disrespectful to the incumbent president and the democratic process. It could also cause public uncertainty about whose guidance to follow—the current or former head of state. Hence, were I former President Jammeh, I would offer counsel and support to my successor without partaking in polarizing political acts. Such conduct would uphold respect for President Adama Barrow and the office of the presidency, while avoiding the spread of mixed signals from previous office bearers.

Former President Yahya Jammeh should refrain from criticizing the current administration to avoid inciting animosity and undermining public trust in the presidency. As a private citizen, it is vital to respect the authority of the incumbent president. Yahya Jammeh could demonstrate exemplary citizenship by supporting the current president’s decisions, even when disagreeing, thus maintaining the dignity of the office and fostering national unity and optimism.

The choice for Yahya Jammeh to retire from politics is ultimately a personal one. However, it is essential to recognize that legal frameworks safeguard human rights, including the freedom of association and political participation. Ideally, Yahya Jammeh may opt to retire discreetly, as other former presidents have done. Nevertheless, given the confiscation and alleged misappropriation of his assets without due process, and the looming threat of international legal action, remaining politically active might appear to be the sole option for self-defense.

Yahya Jammeh, still youthful by political standards, is seen as a potential threat to the regime, with the energy to challenge the government if he so decides, bolstered by the necessary resources and connections.

In contrast, former President Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara has behaved with dignity and honor after his presidency. He has kept a low profile and avoided responding to the numerous provocations from the Jammeh regime, as well as refraining from criticizing the governance of his successor. To motivate and provide incentives for former presidents, the Gambian government enacted a law last year that grants lifetime pension benefits to former presidents. Named The Former President Lifelong Pensions Law, this law aims to offer pensions, gratuities, and other benefits to ex-presidents and their spouses. While it secures financial stability for former leaders, it also carries significant financial consequences for the government and could impact the national economy. The law stipulates a comprehensive benefits package for ex-presidents, including a monthly pension equal to the sitting president’s salary for life. They will also receive a tax-free lump sum gratuity equal to six months of their last gross salary within 30 days of leaving office. A fully furnished residence with utilities is provided, or if they choose their own home, the government will maintain and furnish it as needed. The benefits include personal staff, such as two cooks, four housekeepers, and two gardeners, along with full-time security protection, which is crucial considering potential security threats and the need to concentrate on post-presidential endeavors. Additionally, they will have protocol privileges both at home and abroad, a lifetime diplomatic passport, and extensive medical and dental insurance that covers treatment abroad if required.

Fatoumatta: As the Adama Barrow government is poised to bring Yahya Jammeh to justice and hold him accountable for his actions, one might question whether Jammeh, as a former president, should be entitled to certain benefits. However, his eligibility is mired in controversy due to his legacy, sparking debates over justice and accountability for his past deeds. If the Barrow regime wishes to remove Jammeh from politics, it should stop using the threat of international prosecution as intimidation. Politically targeted individuals tend to respond politically. Jammeh, as an ex-president, still wields some influence, and the current regime’s continued persecution could inadvertently increase his sympathy, undermining their efforts. The government’s most effective strategy against Jammeh would be to outperform him in governance. I advised them upon taking power to avoid actions that would vindicate the former president. Unfortunately, they continue to make this mistake, which may be counterproductive in the end.

Fatoumatta: Key insights emerge from Yahya Jammeh’s interview with The Atlantic. Jammeh, the ex-president of The Gambia now residing in Equatorial Guinea since 2017, still wields influence over Gambian politics through his party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC). The interview sheds light on the intricate political relationships within West Africa, focusing on the interactions between Jammeh, current Gambian President Adama Barrow, and Senegal, with Barrow’s reliance on Senegalese forces for security being a critical element of his leadership.

The discussion with Jammeh provides a crucial perspective on the evolving political landscape of the region. His sustained impact, even in exile, shapes the political dynamics in The Gambia. The interview is a valuable tool for those looking to understand the subtleties of power, governance, and regional diplomacy in West Africa, making it vital reading for anyone interested in the area’s politics.