by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

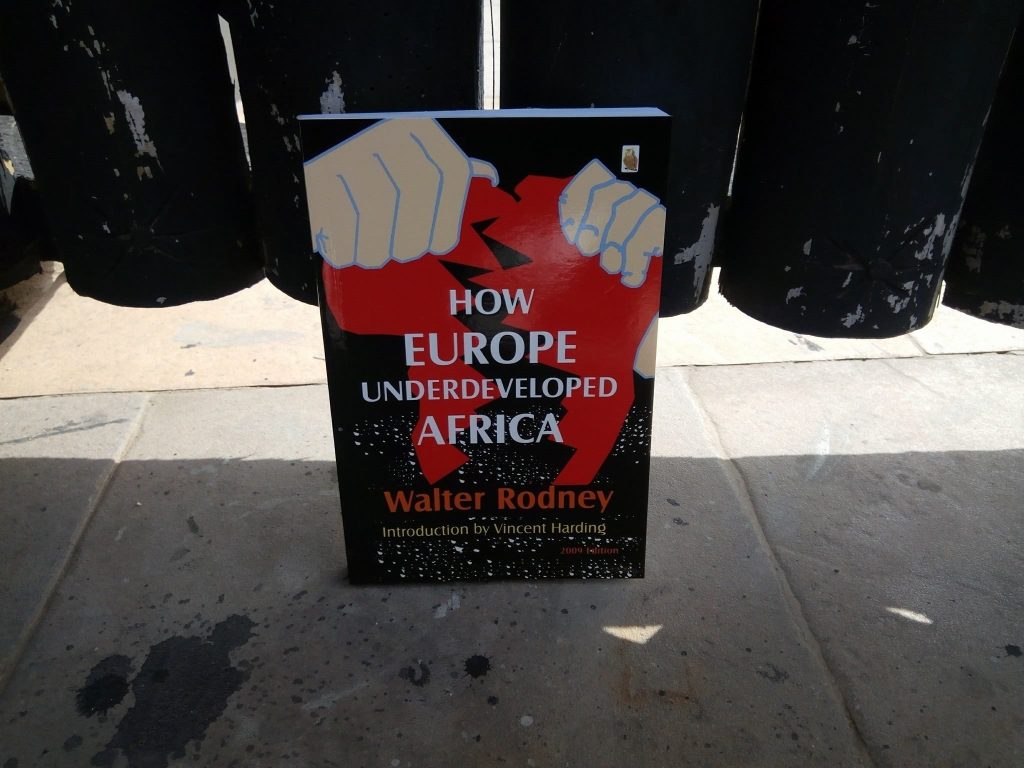

Walter Rodney’s influential work, “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,” remains as pertinent to the African context today as it was upon its release in 1973. In the first chapter, “Some Questions on Development: What is Development,” Rodney offers insightful commentary on Africa’s governance challenges and their effects on wealth generation. Angela Davis provided a compelling introduction to this seminal piece of political, economic, and historical analysis. Rodney, a preeminent Guyanese scholar and activist, became a prominent figure in the anti-colonial movement, influencing North and South America, Africa, and the Caribbean. He became a symbol for working-class Black Power, and his forced removal from Jamaica sparked the significant 1968 Rodney riots. His academic work educated a generation in global political thought. Tragically, Rodney was assassinated in 1980, soon after the establishment of the Working People’s Alliance in Guyana, at the age of 38.

In his seminal work, “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,” Rodney compellingly argues that the significant divergence between the West and the rest can only be understood through the exploitation of the latter by the former. This thoroughly researched examination of the enduring effects of European colonialism on Africa has not only shaped decades of academic study and activism but also continues to be a crucial work for understanding global disparities today.

“It is characteristic of underdeveloped economies that they do not (or are not permitted to) focus on sectors that would spur growth and elevate production to a higher level. There are scant connections between industries, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which could have a mutually beneficial impact on each other.

Moreover, any savings generated within the economy are predominantly transferred overseas or wasted on consumption instead of being invested in productive ventures. Consequently, a significant portion of the national income remaining in the country is used to compensate individuals who do not directly contribute to wealth creation but provide auxiliary services—civil servants, merchants, soldiers, entertainers, etc. The situation is exacerbated by the employment of more individuals in roles necessary for efficient service. These individuals do not reinvest in agriculture or industry. Instead, they dissipate the wealth produced by peasants and workers on luxury items like cars, whiskey, and perfume.

It has been observed, somewhat ironically, that the main ‘industry’ of many underdeveloped countries is administration. Not long ago, 60% of Dahomey’s (now Benin) internal revenue was allocated to the salaries of civil servants and government officials. The remuneration for elected politicians exceeds that of a British Member of Parliament, and the proportion of parliamentarians in underdeveloped African nations is also comparatively high.

In Gabon, there is one parliamentary representative for every 6,000 inhabitants, in contrast to France, where there is one congressional representative for every 100,000 citizens. This is just one of many statistics that highlight the significant disparity in wealth distribution within typically underdeveloped economies, where a small elite accumulates most of the wealth. Defenders within privileged groups in Africa often justify their wealth by claiming that their taxes sustain the government. While this may seem logical at first glance, a closer analysis reveals it as a flawed argument, betraying a fundamental misunderstanding of economic principles. Taxes alone do not generate national wealth and development; rather, wealth is created through the exploitation of natural resources—whether by cultivating the land, extracting minerals, harvesting timber, or transforming raw materials into finished goods for human use.

The vast majority of the population, including peasants and workers, are responsible for the activities that generate wealth. Without the laboring community’s work, there would be no income to tax. The earnings of civil servants, professionals, merchants, and others are derived from the wealth produced by the community. Disregarding the unfair distribution of wealth, it is not sufficient to claim that ‘the taxpayers’ money’ alone fosters national development. To truly pursue development, one must begin with the producers and assess whether the fruits of their labor are being used effectively to enhance the nation’s independence and prosperity.