A Nation at a Crossroads

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

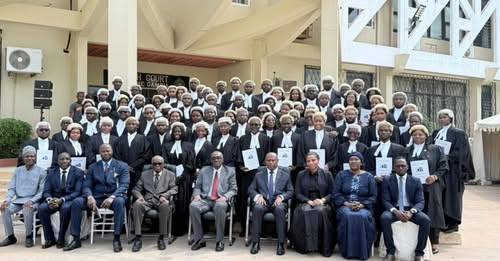

Fatoumatta: Warmest congratulations to the newly minted lawyers who were called to the Bar this Monday. You begin your careers at one of the darkest periods in Gambian legal history. The courts have called you to the Bar, but history has called you to duty. On Monday, the Judiciary of The Gambia admitted 74 new lawyers to the Bar, marking the institution’s fourteenth call-to-bar ceremony. This reinforces the country’s growing legal community, but it also raises troubling questions.

In a nation of fewer than three million people, do we truly need this many lawyers? Or are we producing numbers without purpose, quantity without quality? Passing the bar exam is a source of joy, but the entry of hundreds of new lawyers each year risks creating a paradox: a society with more lawyers than justice. To address this, we must prioritize judicial reform and capacity-building over simply increasing the number of lawyers, especially in a country beset by economic hardship, unemployment, and fragile institutions.

Fatoumatta: Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize–winning economist, warned in The Price of Inequality that countries with fewer lawyers per capita grew faster. Too many lawyers, he argued, divert talent away from innovation in science, engineering, and productive enterprise. His insight applies directly to The Gambia. Instead of channeling our brightest minds into law for law’s sake, we should be cultivating judges, magistrates, engineers, doctors, and educators who build the nation.

African wisdom teaches: “When too many hands stir the pot, the soup will spill.” The Gambia risks spilling its civic soup by producing lawyers without balance, without a vision for justice. The Gambia does not need an endless stream of freelance lawyers chasing cases. What we need is a judiciary that works with more magistrates and judges to expand judicial capacity and reduce backlogs. Modernized courts with infrastructure that reaches every region, so justice is accessible to all. Speedy justice where adjournments are rare, because justice delayed is justice denied. Higher courts of appeal to shield lower courts from being overwhelmed, specialized criminal courts to try corruption swiftly, and tax courts to strengthen revenue collection. This approach can restore hope in our justice system.

Fatoumatta: The discrepancy between our population and the number of judges is glaring. Cases drag on for years, sometimes decades, and are decided without thorough judicial reasoning simply because of time constraints. This is not justice; it is the paralysis of having quantity without quality, which can diminish public confidence. The new entrants must be lawyers who read widely, mainly in history, philosophy, public policy, Shakespeare, and Latin. They must master the English language, have the ability to think critically, and be able to write good English. Developing these skills will help rebuild trust in our legal system.

Too many of our so-called “learned friends” abandon critical thinking for insults, weaponize tribalism instead of debating policy, and wield arrogance rather than intellectual rigor. History shows that good lawyers often make good politicians, because they bring to politics the discipline of logic and a respect for rules. But when lawyers cannot win cases, cannot master grammar, and cannot argue policy, they cannot suddenly become credible leaders.

African wisdom reminds us: “The tongue can build a village, but it can also burn it down.” Our lawyers must choose to build.

Fatoumatta: The decline is visible. Some parade themselves as legal experts yet reduce discourse to vulgarity and tribal smears. This is not advocacy—it is intellectual poverty masquerading as law. Gambians deserve better. We deserve lawyers who embody the nobility of their oath, not those who burn down the village with their tongues.

Insults are not governance. Tribalism is not policy. Arrogance is not leadership. A party that thrives on vulgarity and incoherence cannot claim the mantle of justice or the right to govern. Gambians must demand maturity, intellectual honesty, and dignity from those who wear the wig or else risk watching the law itself become a theater of insults. Our collective voice can push for a more respectful and effective justice system.

The Gambia’s judicial system is floundering, on the verge of capsizing. To rescue it, we must expand judicial quality and capacity. Train impeccable judges and magistrates. Build efficient infrastructure for speedy justice. Reduce reliance on freelance lawyers. Establish specialized courts to tackle corruption and taxation.

Only then can The Gambia aspire to be a democratic society governed by laws, not insults. Only then will justice serve the people rather than burden them. We must support initiatives that enhance judicial quality and capacity, ensuring that our legal system upholds justice and integrity for all Gambians.

Fatoumatta: The future of The Gambia depends not on the number of lawyers we produce, but on the quality of justice we deliver. Let us remember: “A tree is judged not by the number of its branches, but by the sweetness of its fruit.” May our judiciary bear fruit that nourishes democracy, protects the vulnerable, and strengthens the rule of law.