Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Fatoumatta: In Antonio Gramsci’s prison notebooks, he describes the “monster” of Gambian democracy, particularly in Notebook 3, where he notes that during crises, “the old order is dying, the new order is slow to appear and, in this chiaroscuro, monsters appear.” This monster is more daunting than fascism, populism, and violence, which are often just the collateral damage of politicians’ intimidation games. The real monster is the unsustainable cycle of “Taa Ning Naa” (coming and going) between the heights of democratic ideals and the low points of a society in democratic transition. Our democracy, though nascent, has reached its zenith by adopting the finest global democratic standards, overcoming a deep-rooted dictatorship, and electing a President in 2017 and again in 2021 without disrupting state continuity, except for the brief political impasse created by dictator Yahya Jammeh, who refused to relinquish power to Adama Barrow, who was democratically elected in a free and fair transparent election. This election is described as one of the most hailed elections in Africa when a coalition of the opposition defeated an entrenched incumbent dictator with all the advantages of incumbency. This is a testament to our democratic system’s strength, where individuals and regimes may change, but the state endures.

However, we are now descending into the depths of societal slums amidst a democratic transition, where the judiciary faces relentless attacks, and its justices are belittled daily on social media, undermining the pillars of republican independence—this is anarchy. We had to brace ourselves, for the “Taa Ning naa” is swift, brutal, and violent. In a democracy like ours, one of the oldest on the continent before the 1994 military takeover, which has hosted the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, the custodian of the Banjul Declaration, and the African Center for Democracy and Human Rights Studies, the call for a charter of non-violence marks a significant regression, a throwback to the “era of the democracy of the furies.” This chapter was thought to be concluded with the political changes of 2017 and the Presidential and general elections of 2021, when Gambians recognized the ballot box’s power over fury.

Fatoumatta: Following the end of Yahya Jammeh’s rule, the 2021 elections saw the opposition secure a significant victory, obtaining the majority in the mayoralty of the capital Banjul, the Kanifing Municipal Council, and for the first time in history, in key cities such as Brikama, Mansa Konko, and Basse. This marked a historic moment, confirming a shift in political power. Additionally, for the first time, the opposition gained a significant majority in the National Assembly since the restoration of democracy in 2017. In the same vein, The Gambia maintained its status as a leading democracy, with performance indicators comparable to those of Great Britain or Scandinavian countries, particularly when the opposition took an electoral dispute to the Supreme Court for resolution. Thus, The Gambia has achieved democratic progress, blending the British standard of judicial resolution of political disputes with the Congolese approach of discussing a non-violence charter.

In a true Sisyphean democracy, there’s an attempt to blend the dust of the Colosseum and its gladiators with the marbles of the Senate. Our democracy should evolve past the gladiator era, which began in the 60s and ended in 2017. Fatoumatta: Post-2017, the gladiators ought to have been succeeded by an “aristocracy of orators,” competing through ideas and social initiatives. In this phase of democracy, electoral disputes are resolved in courts, not through street power struggles reminiscent of gladiator times. The current turbulence does not stem from institutional or political issues; rather, it originates from a manufactured tension that benefits all parties involved. This tension enables civil society to play a crucial mediating role, while allowing politicians to avoid urgent matters, such as the persistent threat of terrorism and the essential journey towards peace after overcoming the fear of despotism. It is imperative strive for a triumph for democracy, promoting a politics of infrastructure development and economic growth will elevate our capital city to become a true beacon of modern democracy.

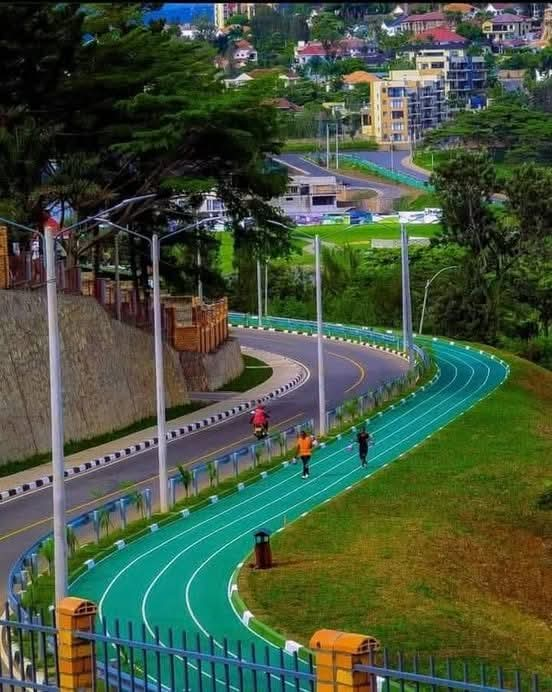

Fatoumatta: In our new democracy, we have the incredible opportunity to transform Banjul into a city brimming with tourist attractions, vibrant nightlife, beautiful sidewalks, engaging entertainment, and cleanliness akin to Kigali. This ambitious vision can become a reality and serve as a remarkable dividend of our democracy through strategic action. Investing in well-paved sidewalks and roads will not only enhance safety but also inspire more walking and reduce traffic congestion. By developing a reliable public transportation system, we can lessen our dependency on personal vehicles and elevate mobility for everyone. Imagine mandatory community cleaning days that empower residents to take pride in maintaining their neighborhoods. With robust waste management programs, including recycling and proper disposal, we can foster a culture of cleanliness. Regular cultural events, lively festivals, and captivating concerts can draw in both locals and tourists, while designated and safe nightlife areas will invigorate our social scene. Building recreational facilities such as sports complexes, theaters, and community centers will enliven our city further.

Fatoumatta: Let us unite with private businesses and international organizations to fund and support these transformative initiatives. Attracting investment in infrastructure and entertainment will fuel economic growth and create jobs. Educating our community on the importance of cleanliness and civic responsibility will instill pride in our city. Involving community leaders and residents in the planning and execution of projects ensures we are meeting the needs of our people. Together, by embracing these steps, we can elevate Banjul into a vibrant, clean, and enjoyable city, reminiscent of Kigali. This journey requires our unwavering dedication, resources, and the collective effort of the government, private sector, and citizens. The transformation we envision is within our reach, and the results can be nothing short of extraordinary.

Fatoumatta: In conclusion, Gambian democracy has made significant strides by overcoming dictatorship and achieving democratic progress through successful elections and judicial resolutions. However, challenges remain, including attacks on the judiciary and societal instability. By embracing strategic steps to transform Banjul into a vibrant, clean, and enjoyable city, The Gambia can further solidify its democratic achievements and provide tangible benefits to its citizens. This transformation requires the collective effort of the government, private sector, and citizens, but the results can be transformative and serve as a testament to the resilience and potential of Gambian democracy.

Photograph: The Rwandan capital, Kigali, after the 1994 genocide.