Fatoumatta: Violence is never a solution in Gambia. The Italian Marxist philosopher and journalist Antonio Gramsci, in Notebook 3 of his prison writings, observes that crises occur when “the old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born; in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” The real threat to Gambian democracy is not violence, which often serves merely as collateral damage from politicians engaging in games of intimidation and then becoming scared themselves, akin to children. The real threat is the unsustainable oscillation between the heights of democratic ideals and the lowly slums of a society undergoing democratic transition. Our democracy reached its zenith when we demonstrated to the world how to overthrow and replace the last African dictator, who had ruled with an iron fist for over two decades, with a President elected through a free, fair, and transparent process, acclaimed as one of Africa’s finest electoral models. This seamless transition of power, without any disruption to state continuity, is a testament to the strength of our democratic institutions, where individuals and regimes may change, but the state endures.

Fatoumatta: We are descending into the depths of societal decay during a democratic transition when opposition politicians are arrested for sedition by insulting the president, a colonial law heavily criticized and deemed unconstitutional in many African countries, including the Supreme Courts of Lesotho and Kenya. Our democracy, one of the oldest on the continent, has been tarnished by the military’s intervention in 1994. Yet, it has been honored as the host of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights and the African Center for Democracy and Human Rights Studies in the Gambia, a beacon for Africa and a treasure for the Gambia. Debating the need for a non-violence charter represents a significant regression, a throwback to the “era of the democracy of the furies,” which we thought ended with the peaceful transfer of power in 2017. The Gambian people realized then that the ballot box was more potent than fury. Nevertheless, the Gambia has maintained its status as a leading democracy, comparable to Great Britain or the Scandinavian nations, especially when the opposition took an electoral dispute to the Supreme Court. Since the ousting of dictator Yahya Jammeh in 2017, the Gambia has balanced the British standard of resolving political disputes through the courts with discussions on a non-violence charter.

Fatoumatta: In a democracy reminiscent of Sisyphus’ endless struggle, there is an attempt to merge the Colosseum’s dusty arena, with its gladiators, with the polished marbles of the Senate. Our democracy should evolve past the gladiator era, which began in the 60s and ended in 2017. Since then, the role of gladiators ought to have shifted to an “aristocracy of orators,” who vie through ideas and social initiatives. In our current democratic phase, electoral disputes are resolved in courts rather than through street power struggles, as was common in the gladiatorial period. The current turbulence we experience is not institutional but political, stirring a Monster that benefits all: the manufactured tension that keeps civil society engaged in mediation and allows politicians to sidestep pressing issues. These issues include the pervasive threat of terrorism, establishing peace in neighboring nations following the Gambia’s successful hosting of the OIC, and the unique challenge of providing sidewalks in Banjul, the only capital without them.

Reports and observations indicate that the Gambian social and republican model has endured the blind violence of those who have shifted from electoral competition to the destruction of societal frameworks. The silence of prominent members of Gambia’s intellectual, religious, and elder communities, some of whom have even justified these acts, is particularly disheartening.

There seems to be an intent to dismantle the social fabric by instilling the seeds of civil strife within the populace, especially the youth, through divisive ethnic and political rhetoric. The cherished collective aspiration for coexistence is now at odds with their agenda to fragment the nation and undermine its political and economic unity. The republican model is under siege; since their emergence in the public sphere, they have consistently undermined its tenets, assailed its principles, and exploited prevailing discontent to erode the bonds that form our democratic society, which values public freedoms and honors cultural diversity. The political landscape has been tainted by certain politicians and social activists, who represent a confluence of populism and radical ideologies, both aiming to hollow out the Republic’s core, destabilize its structure, and deliver a crippling blow before the upcoming elections in two years.

Fatoumatta: Populist politics and hate speech have not succeeded, as our nation, since Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara’s time, has established a resilient state that has endured all forms of aggression and threats. The Gambia has remained a bastion against the spread of the Islamist hydra. It has overcome a malevolent military coup and a harsh dictatorship that persisted for twenty-two years, only to be overthrown by a transparent election in 2017. Current efforts to resurrect it through political means are likely to fail. However, the question remains: how long can our country hold out? The defenses are weakening; the republican spirit is eroding, and intellectuals are faltering due to fear, cowardice, and opportunism. Journalists have shifted from seeking truth to echoing an overtly fascist agenda. In contrast, the governing body’s lack of statecraft, seriousness, and preoccupation with trivial political matters in the face of grave threats has been both surprising and concerning. Their focus is detached from the actual problems and challenges that our nation faces, surrounded by a volatile region and threatened by the deep infiltration of the state machinery by foes of democracy, secularism, and the Republic.

High public office is often perceived as a privilege, but it is seldom acknowledged as a responsibility—an obligation to serve the State and uphold the republican legacy bequeathed by our forebears, who sacrificed so much for our flag’s continued presence. Choosing the right adversary is crucial. Amidst seditious violence and the rise of populism within the state’s core, I understand how to position my adversaries, distinguishing between those aligned with the republican trajectory and those who are not, whether by choice or intellectual deviation. As we approach the 2026 presidential elections, with the incumbent potentially seeking a third term, it’s clear that the roots of such aspirations lie in a refusal to adhere to democratic principles, a penchant for sedition, and the systematic use of ideological and political shields. The tradition of power remains etched in my memory.

Fatoumatta: My life’s struggle is against fascism, and I have chosen republican socialism, which holds the Republic’s sanctity, economic accountability, and social progress as its core. In these uncertain times, I remember that one does not engage with another adversary when fascists loom at power’s threshold. Fascism, representing foes that must be combated with vigor and responsibility, should not lead us to forsake legal instruments and rational political discourse.

To keep the banners of democracy, liberty, and social advancement aloft after facing down the threats to our national unity, social fabric, and the Republic’s sanctity, republicans across the political spectrum must unite against this near-civilizational threat. I claim no authority to instruct others. Yet, I echo Annie Ernaux’s sentiment: “I write to avenge my race.” Thus, I call upon the political and intellectual elite. They have lost their way, surrendering to a political stream that has opposed us for two centuries—a stream fostering fanaticism, obscurantism, and hostility towards enlightenment, education, and culture. The Gambian political and intellectual lineage, with its commendable social and democratic legacy, has partly succumbed to maneuvers and global shifts, leaving progressives with scant opportunity worldwide.

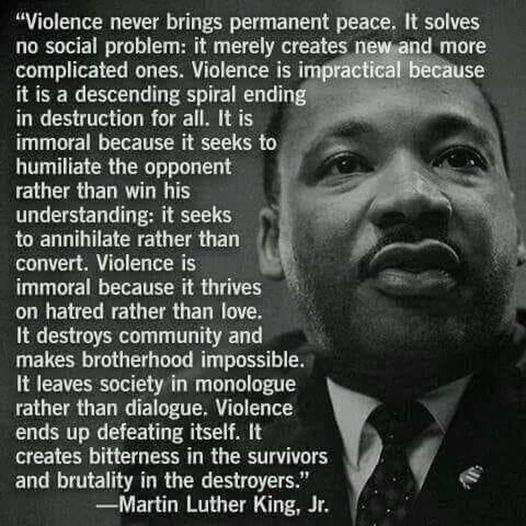

Fatoumatta: What disheartens me is the intellectual class’s decision not to align with civil society while maintaining its identity, but rather to follow the lead of populism without question. This choice, driven by hatred for one individual and a chaotic illusion, has led to organized sedition. I find myself disillusioned with intellectuals and eminent figures I once held in high esteem, to the extent of having pledged to campaign and co-author articles with them. I must remind this intellectual class: violence is never a justifiable or sustainable option. In violent conflicts, it is often the best activists who perish. Moreover, it is the common people, those from working-class backgrounds, the vulnerable, and the precarious, who suffer the greatest consequences. I am from the ranks of the vulnerable, the overlooked, and the impoverished. A profound sense of melancholy connects me to those who have fallen victim to violence, often without understanding its political underpinnings. Whether they are well-educated, middle-class professionals, intellectuals longing for chaos, social media drifters, Gambians in the diaspora inciting violence from Europe and America, or expatriates ensconced in affluent areas who display disdain or patronizing attitudes towards the populace, their accusations do not affect me.