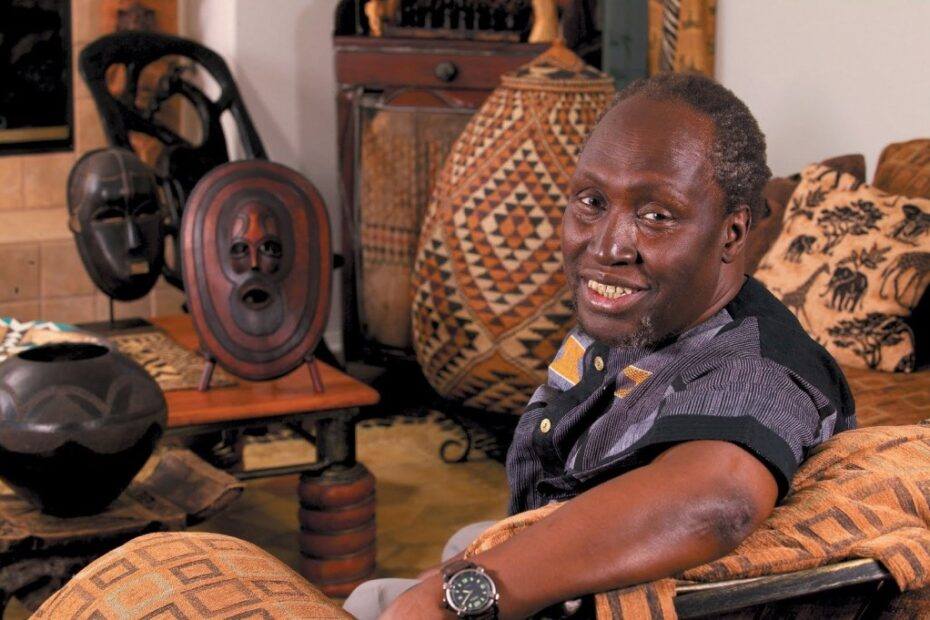

Fatoumatta: Long overdue, Ngugi wa Thiong’o will be honored in Atlanta, Georgia, on June 22, 2024, for his lifetime achievements in literature. On that day, Africans and Kenyans in the Diaspora, especially in North America, will celebrate our most distinguished living writer: Ngugi wa Thiong’o. While Ngugi has received accolades globally, Africa and his homeland, Kenya, have yet to fully recognize his contributions. I have often questioned why Ngugi wa Thiong’o has not been given the recognition he deserves, given his vast contributions to literature, his dedication to promoting our mother tongue, his activism against dictatorships, and his example of the sacrifices writers of his era had to endure, such as exile. He was instrumental in shifting the focus of the Department of Literature at the University of Nairobi from a Eurocentric emphasis on 19th-century European literature to an Afrocentric perspective that celebrates our literary works. I regard Ngugi as Africa’s foremost philosopher of decolonization. Reading his collection of essays, ‘Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature,’ is transformative.

The novelist, thinker, and philosopher has become a global icon, with his works garnering both high praise and intense debate. His only peers on the continent are Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. It’s not that Africa and Kenya fail to recognize Ngugi; people are aware of his identity and contributions. However, those in positions to honor him often hesitate to do so due to reasons ranging from tribalism to professional jealousy and other trivial matters that are ultimately nonsensical. Should the unthinkable happen and we lose him, there would likely be an outpouring of insincere grief and posthumous tributes, which is utterly indefensible. It is often said that we should “give people their flowers while they can still smell them,” to let them know they have made a difference during their time on earth. This is precisely why the Kenya Diaspora Alliance-USA has taken the commendable step of celebrating Ngugi at a significant venue like Georgia State University in Atlanta, USA. The assembly of academics, literary scholars, writers, readers, friends, and fans to honor Ngugi and his work was indeed much needed.

Fatoumatta: One cannot truly grasp Ngugi’s impact until they travel abroad and hear how works like “Weep Not, Child” or “A Grain of Wheat” have profoundly affected others or shed light on the severity of the Mau Mau conflict. Many are unaware that the British were exceptionally brutal to the natives in Central Kenya, a colonial cruelty on par with American slavery or South African apartheid.

In the USA, I encountered two South Africans who expressed deep admiration for Ngugi. I recall when Ngugi visited Harlem, we, as African students burdened with a heavy graduate workload, yearned to attend but could due to number of people in attendance without ticket to get into the lecture hall. I also met two Indians who were more familiar with Ngugi’s works than I am: an editor from a Delhi newspaper and a fellow graduate student. Ngugi’s influence extends to younger African writers like Chimamanda Adichie, who regard him as an inspiration.

Fatoumatta: Over the past decade, Ngugi has frequently visited Africa, engaging with various universities and communities, launching his books, and debating his ideas. Despite the complexities of exile and the difficulty of relocating, he has remained committed to the African cause, always speaking his mind. With age, he has become more gracious towards those in power.

Ngugi, like any human, is neither perfect nor are his ideas beyond dispute. His flaws and complexities make him human.

As those in the Diaspora honor him, I hope like-minded Kenyans and Africans will recognize the need to commemorate Ngugi. Honoring artists and authors is a political matter, and some expect them to be saints, flawless, and to fulfill a certain standard before they can be celebrated. It’s particularly challenging in Africa, but it’s necessary nonetheless. Africa needs more thinkers and fewer plunderers. A dozen years ago, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was in Harlem, not far from my school, for “Revolution Books and the Emancipation of Humanity.” I admire Professor Ngugi; to me, he is an African treasure. I often wonder why we don’t have a Ngugi wa Thiong’o library, theater, or a dedicated section in any of our American Literature departments, especially at universities offering African Literature. Ngugi’s visit to Harlem was a symbolic act and a significant honor. Regarding Harlem, it’s commonly known as the world’s largest ghetto, but that’s no longer the case. In the 1970s, as Bobby Womack articulated in his soundtrack for the film Across 110th Street, “it was one hell of a tester.” The song depicts Harlem at that time, with Womack singing, “In every city, you find the same thing going down; Harlem is the capital of every ghetto town.” It was a Mecca for the black race.

Fatoumatta: Over the past decade, gentrification has transformed the neighborhood; it’s no longer the exclusively black community it once was. (Note that there is a Spanish Harlem in the eastern part of Harlem). Since 2001, the black population has decreased from 90 to 60 percent and may continue to decline as rents soar to exorbitant levels, a hallmark of Manhattan living. Consequently, many black residents can no longer afford to stay and are forced to relocate.

This change stands in stark contrast to the past. Following the civil rights movement, and the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, Harlem descended into a state of drugs, crime, and urban decay, exemplifying the merciless nature of capitalism. Manhattan, one of the world’s wealthiest areas, juxtaposed with the historic ghetto within the same borough, presented a profound contrast.

Yet, Harlem has preserved its historical importance to the black community. Its main thoroughfares and edifices bear the names of civil rights leaders and the esteemed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. This is the neighborhood where Ngugi found himself.

In New York, Ngugi’s work is greatly esteemed. There’s nothing amiss with Ngugi sharing literature rooted in his heritage. I am among those who believe one can be a proud African, American, and Gambian all at once.

Ngugi stands as a pillar of thought and literature. His works, though ethnically Kikuyu, resonate universally. Affected by colonialism, he writes from a place of authenticity, not an idealistic vacuum. After all, writers are storytellers of their own truths.

Fatoumatta: I find pleasure in reading books that engage me on three levels: the witty, humorous, and satirical; the intellectual and philosophical; and the emotional. Ngugi’s work resonates with the latter two, and his novels and short stories, particularly those addressing humanity’s betrayals, can subtly convey humor. ‘The Martyr’ is one such example. Ngugi’s prose poignantly conveys the atrocities of colonialism, the dispossession of land, and the complex legacy of British influence in Kenya, both positive and negative.

Ngugi’s essays, especially ‘Decolonizing the Mind,’ are essential reading for every college freshman. His advocacy for the use of mother tongues, while seemingly impractical, holds merit. Africa suffered greatly from the loss of its languages and the imposed belief that speaking them was regressive. The thought of those language-discouraging practices still angers me. It would be a grave human rights violation if children were still coerced into speaking only Swahili and English, judging their intelligence by their proficiency in ‘proper’ English.

English serves as a practical lingua franca for a continent rich in linguistic diversity. In countries like Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania, local languages flourish, with literature and newspapers thriving in these tongues. The Gambia, too, fares well. Our music, often overshadowed by foreign influences, deserves recognition. Despite the DJs’ shortcomings, they reflect a cultural preference. Language is a potent cultural element, fiercely protected by the world’s leading economies.

Fatoumatta: I hope for more thinkers like Ngugi in The Gambia, not necessarily for their infallibility, but for their ability to provide a framework for our national aspirations, steering clear of astonishing follies.