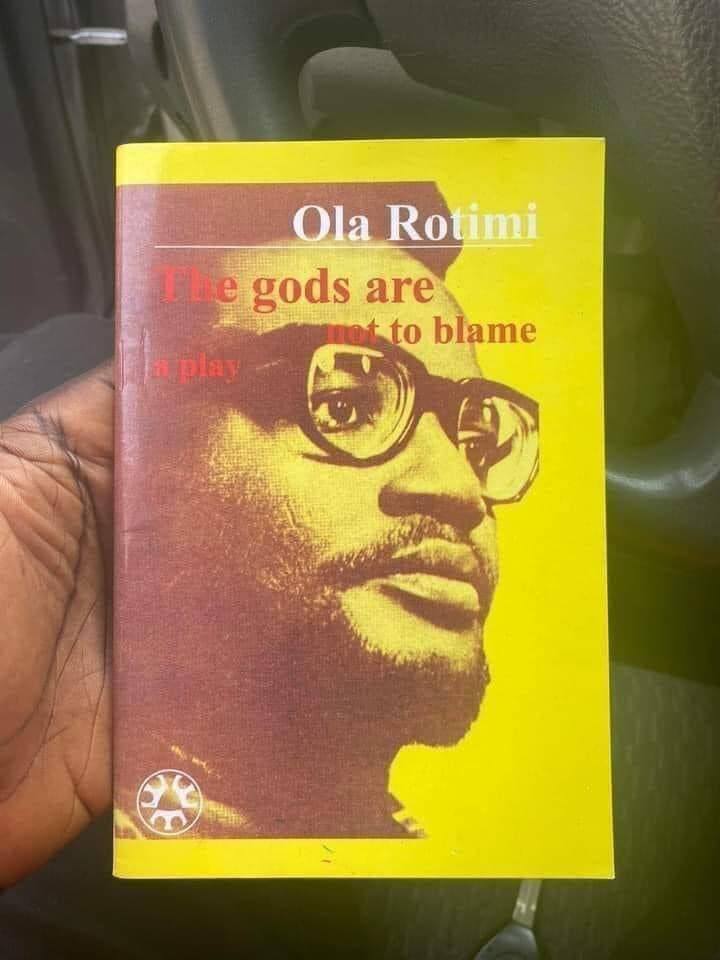

by Ola Rotimi

Review Alagi Yorro Jallow.

Fatoumatta: Some memorable sayings from the novel “The Gods Are Not to Blame” include: “The struggles of a man begin at birth,” “The future is not happy, but to resign oneself to it is to be crippled fast,” and “He who pelts another with pebbles asks for rocks in return.”

These sayings, among others, are woven into the narrative of Odewale, who is drawn into a false sense of security, only to become entangled in a web of events marked by consanguinity. This classic book was one of my favorites from my high school literature class.

This novel, a 1968 play turned into a 1971 book by Ola Rotimi, is an adaptation of the Greek tragedy “Oedipus Rex,” set within a Yoruba kingdom, and remains a distinguished work in African literature and a personal high school favorite.

“The Gods Are Not To Blame” is Ola Rotimi’s retelling of Sophocles’ “Oedipus The King” using a traditional African setting and characters. Through this book, I first became acquainted with Oedipus’ tale. However, what really stricks me about this book now is Rotimi’s title. Like Sophocles, an ancient Greek tragedian whose plays have survived. Ola Rotimi’s tale is about a man’s struggle to avert fate. But unfortunately, in the process, it helps to bring about its fulfillment. That is why “The Gods Are Not To Blame.”

Though it portrays the African Traditions, there is a lot to learn from irrespective of whom you are and where you come from. “Kola nut indeed, last longer in the one who cherishes it.”

I remember our teacher, Mr. Gabriel Roberts, reading African Literature class. After we had finished reading the book, discussion and analysis were the following things up the list of things to do next. And so we did that. The question thrown out to us for dissection by Mr. Roberts was: Are the gods to blame?

Fatoumatta: I will tell you exactly why this book is memorable. But first, If you know this book: Oedipus Rex, you already have an idea of what this story is about, its implications, the cruelty of its tragic plot, and the amount of debate the question above presents. A boy destined to succeed, be a king and be great, kill his father, and marry his mother—a boy who would be the author of many tragedies.

Did the gods watch in mild amusement as humans tried to undo this monstrous prophecy by decreeing that the boy be killed when he was born? And were they fascinated by the blind confidence of men and the uselessness of their fumbling schemes as they failed and the boy survived? Did they smile sinister, knowing smiles as the die was cast? I prefer the original from which this story was adapted. Oedipus Rex was one of the books I read as a little boy. Unfortunately, I only remember bits and pieces from it. But I love it still. I loved it the first time I read it for my literature class in high school and found myself with so many fond memories as I reread it as an adult. The themes are even more poignant as I viewed them through a different/more mature lens, and the writing is even more potent than I remembered.

Fatoumatta: This is one book that will always stay with me. I’ll be eternally grateful to Mr. Gabriel Roberts. In Ola Rotimi’s version of the Greek mythology about cursed Oedipus, we see a relatable Yoruba man named Odewale – a strong-willed man who becomes the very thing he ran away from. For those unfamiliar with Oedipus’ story, it is a myth about a mortal who was cursed to kill his father, marry his mother, and bear four children. A chilling taboo. His parents tried to stop fate by decreeing his death at infancy. So begins the tragic tale that leads to heartaches, deaths, and sorrows, with readers asking, “who’s to blame?”

In The Gods Are Not to Blame, Rotimi gives the ageless story a new spin, a fresh perspective that makes his book a classic. Focusing on the Yoruba tradition, Ola Rotimi spotlights Yoruba gods, giving Sango, Orunmila, Ifa, and Ogun prominent roles throughout the book – as King Odewale, King Adetusa (Odewale’s father), Queen Ojuola (Odewale’s mother), Aderopo (Odewale’s brother), the Chiefs and other characters in the book refer to them often.

While this book is similar to the original Greek story, it finds its originality by adding different elements and characters. An example of this is how it sticks to the King being killed where three roads meet, and the four kids begat by mother and son. Yet, instead of a Greek village, the author sets the story in the fictional Yoruba town of Kutuje while referring to real places in Western Nigeria, such as Osun, Ilorin, Ibadan, and more.

Odewale’s character experiences different phases of confusion, almost painful in its helplessness. Finally, the reader will become sympathetic to his plight, cursing fate for dealing with such a heavy hand.

Fatoumatta: Suppose you compare Rex Warner’s Oedipus story (in Men and Gods) to Ola Rotimi’s The Gods Are Not to Blame. It is straightforward to see the mythical story’s differences (and familiarities). In the former, Laius (Oedipus’s father) was told by an oracle that his son, yet unborn, would kill him; whereas in The Gods Are Not to Blame, the revelation comes from Baba Fakunle, an Ifa Priest, who sees into the future of the newborn baby in his arms. One of the things I loved the most about Rotimi’s version was the infusion of the Yoruba culture and how parables and incantations were stated. Odewale was in touch with his supernatural side and was quick to call on Ogun, going so far as to swear on the deity, which eventually led to his downfall.

It was also interesting to see how Odewale’s destiny led him back home, especially when he became a good ruler. The Gods Are Not to blame is full of irony, despair, and disillusions. In the end, the reader is left with a ringing conclusion – one can never outrun fate.

Fatoumatta: At the time, I thought(and still think) the title of the book: The Gods Are Not To Blame, wasn’t a bold declaration by the author even if it simply presented itself as such – but instead, it was the exact opposite, an open question in disguise, delivered for thought—an atmosphere for doubt and pensiveness. I thought about it(and not for long because I knew my answer from the first page to the very last page) and maintained what I saw as the truth long after putting the book down. My response was negative. They were to blame goddamit. They were full of blame, stinking and rotting from it. They decided the fates, and they presented you with a false sense of choiceness, an empty, cruel gesture. Daring you to outsmart, thwart, and evade the cunning lord, Kismet.

But we were having a discussion, and like all discussions, contradicting opinions were guaranteed. Finally, my closest friend answered his opinion, which was strongly opposed to mine. And let me tell you something, that was the year of hormones. Of course, they were to blame! And this led to another question: Are we the writers of our destiny? Do we make our destiny out of a few choices and nothings, or are we still unwittingly playing into the clammy hands of fate, believing these – the lives we live – are all our crafts? I refused to be faulted for what came next: One word led to many, and many words led to a sentence. And before anyone could put the flame out, it turned into a wild, poisonous fire. The whole class was screaming at and yelling over each other. For a while, African Literature class was a silent graveyard only disturbed by the swish-swosh of pens dragging across papers. Students robotically took notes and analyzed thoughts dictated to us by our teacher. There would be no discussion if we weren’t mature enough to handle a debate. But nobody agreed to take the fall for that moment of madness. It was the hormones, and along with them came pride. Years later, I’m still pondering the same questions. After going over it again, I don’t know how Fatoumatta: I feel about this book. I know that people got screwed over, and some people in high places enjoyed doing the screwing. The play is a great read, one that will have you envisioning every aspect of it, making it seem that you are watching a theatre performance. A classical tale (play here) transposed onto African soil, as it were. An ending that breaks one’s heart. The dialogue is colorful, fecund, brimming with camaraderie and superb work with Rotimi.