Reviewed by Alagi Yorro Jallow.

“The Dragon’s Gift: China’s Debt Diplomacy” by Deborah Brautigam is a book that every Gambian activist, business journalist, political leader, and public intellectual should consider essential reading. It provides a dire account of China’s strategy to ensnare developing African nations with enormous, unsustainable loans collateralized by vital assets. Such debts could serve as powerful leverage for China in negotiating specific concessions.

While the book is compelling, it may not appeal to a broad audience due to its length and scholarly nature; only those with a keen interest in the subject will likely appreciate it. My own interest in the topic was piqued by my experiences in Malawi, Zambia, and Uganda, where I observed China’s involvement with Africa and encountered many of the misconceptions that the author addresses.

Deborah Brautigam, a distinguished scholar, highlights several key points regarding China’s involvement in Africa: the figures often cited may be exaggerated, duplicated, or simply wrong. While China is a significant donor and investor in Africa, the collective contribution of Western countries is still considerably larger. China’s engagement with Africa is not a recent development; it has a long history that was largely overlooked by the West in the past.

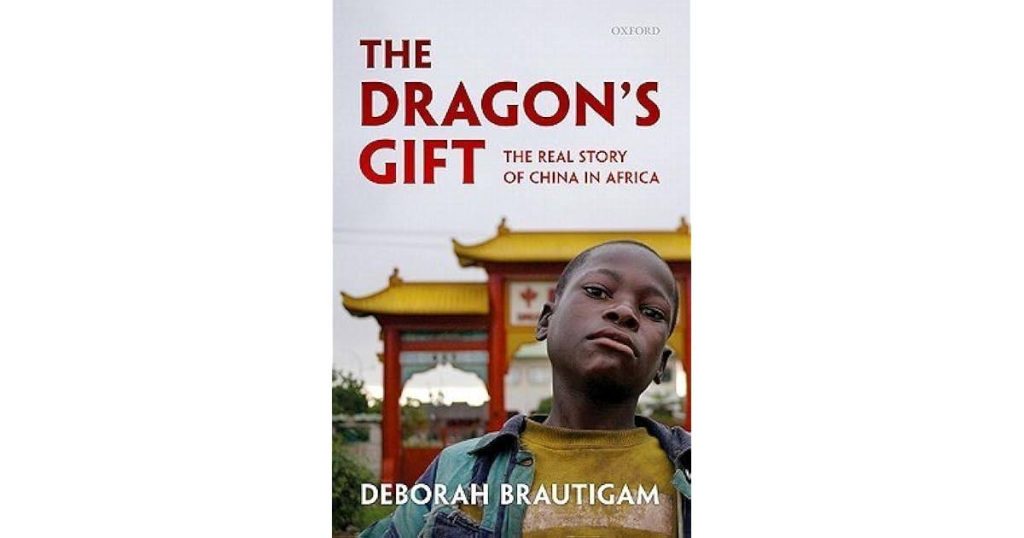

“The Dragon’s Gift” alludes to China’s method of providing foreign aid and fostering economic cooperation, especially in Africa. This subject has been thoroughly investigated in various studies and publications, including Deborah Brautigam’s “The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa,” which offers an in-depth analysis of China’s aid initiatives, dispelling misconceptions and clarifying the true nature of China’s involvement, its execution, the extent of aid provided, and its role in China’s broader global agenda.

Min Ye’s empirical study, “The Dragon’s Gift: An Empirical Analysis of China’s Foreign Aid in the New Century,” delves into the progression of China’s foreign aid policy and its broader implications. Utilizing data, the analysis reveals both parallels and distinctions between Chinese and Western benefactors, positing that China’s foreign aid is indicative of its unique position as both the largest developing nation and a rising international force.

These resources offer valuable perspectives on the debate surrounding China’s foreign aid practices, often labeled “debt diplomacy,” which raises concerns about the potential to create dependency or exert undue influence through financial assistance. China’s involvement extends beyond merely extracting resources for its markets, contrary to common accusations. China’s investments span numerous countries and sectors, focusing primarily on profits, businesses, international brands, and exports rather than just resources like oil and copper. Many practices attributed to China, such as tied aid, resource-backed loans, and export and import credits, are in fact learned from Western countries, which have engaged in similar practices until recently, and some continue to do so. Therefore, China cannot be singled out for criticism without also acknowledging the role of the West. A significant portion of China’s aid and investment goes into infrastructure and manufacturing, areas that require more attention from Western countries. China aims to create a mutually beneficial situation with its aid and investment efforts.

The book presented a captivating exploration of enlightenment, challenging numerous myths and highlighting the positive aspects of China’s actions. China is often misunderstood, a situation largely attributed to its lack of transparency.

What I found most intriguing was the book’s examination of Chinese perspectives on aid and investment. China stands out as a developing nation that extends assistance and investment to other developing countries, which is a departure from the norm of developed countries doing so. This distinction influences their perspective and methodology. The book illustrates this through China’s evolution in providing aid, shaped by its experiences, and its critical view of Western paternalism, exemplified by conditionality and structural adjustment. It was thought-provoking.