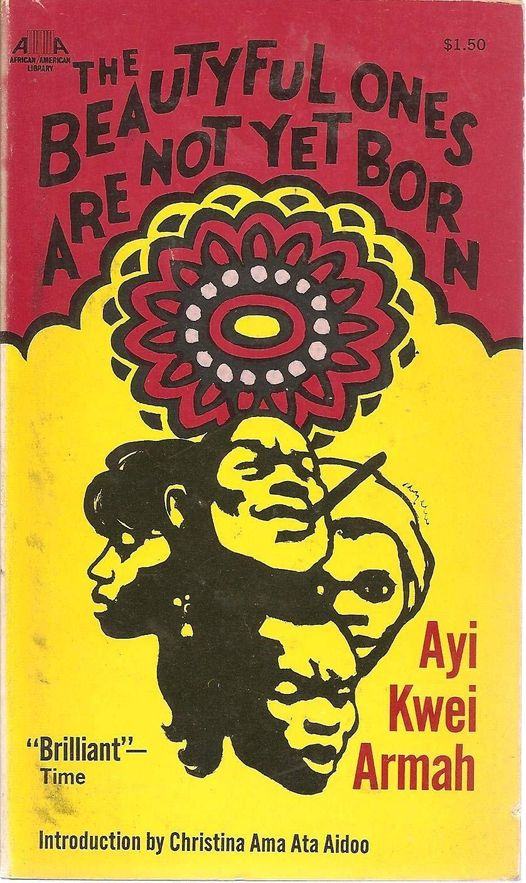

by Ayi Kwei Armah

Review by Alagi Yorro Jallow

Fatoumatta: Ghanian author Ayi Kwei Armah is a legend and one of the best ink molders of all time. “The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born” is a hard-to-avert prophecy from a lamenting patriotic seer and ink bender who sits on the tallest African tree.

This is Armah’s first novel added to Heinemann’s African Writers Series, and I am so glad that I have read and reread it. The novel is seriocomic, a satirical attempt at showcasing the irony of Nkrumah’s leadership (and if you are familiar with Ghana during the Nkrumah years, you see why this is ironic indeed). In addition, it is an attempt to broadcast the voice of Ghana that was usually unheard: that of the poor–in most cases uneducated–village workers. This novel is about the dung of life, and so it is not surprising that no words are minced:

“Left-hand fingers in their careless journey from a hasty anus sliding up the banister as their owners returned from the lavatory downstairs to the offices above.”

You may be tempted to stray because this character-driven narrative has a couple of perspective switches and some brief philosophical meanderings that will, at first, seem daunting. Stick with ‘the man,’ however, and you should be fine, for he (as well as his book-addict “teacher”) will tell you the blatant truth:

“If you come near people here, they will ask you, what about you? Where is your house? Where have you left your car? What do you bring in your hands for your loved ones? Nothing? Then let us keep quiet and not get close to people. People will make you sad that you do not have a house to make onlookers stumble with looking or a car to drive every walker knows that a big man and his concubine have just passed. So let us keep quiet and watch”.

Fatoumatta: This book changed my perception of Africa as much as Things Fall Apart. I was startled to realize, through these books, that I had never imagined everyday life for people in Ghana, had only thought of Africa through adverse news reports and famine relief appeals, and had never considered the possibility that Africans might live in cities go to work in intelligent clothes and drive cars. Such is the power of ethnocentric socialization. Very intense and intensely written. Also beautifully written book.

I could only absorb about one chapter a day, both content and language. Occasionally Armah gets carried away with an elaborate metaphor or description, but generally, it works. In Ghana, a railway freight clerk attempts to hold out against the pressures that impel him toward corruption in both his family and his country. The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born is the novel that catapulted Ayi Kwei Armah into the limelight. The novel is generally a satirical attack on Ghanaian society during Kwame Nkrumah’s regime and the period immediately after Independence in the 1960s. It is often claimed to rank with Things Fall Apart as one of postcolonial African literature’s high points.

Fatoumatta: A brilliant read. Armah teaches us how to use literature as a powerful device to assert social change. The protagonist, an unnamed man, is a quintessential worker in a railway station whose values collide with neo-colonial Ghana’s pervasive corruption and decay. He represents the working class of postcolonial Ghana: potent and steadfast. “The man,” along with characters such as “Maanen, Kofi Billy, the teacher, and others,” are fascinatingly explored in this novel for their resistance to what seems to be the only way to “the gleam”: material wealth. They differ for not accepting that “a man’s value could only be as high as the cost of what he could buy.” (Armah: 134/1968). Their resistance is not a revulsion against attaining luxurious commodities, notably the television or stereo, but to the corruptive way to attain it. I enjoyed the ironic reversal of roles between Koomson and our protagonist: the once-influential minister to a man pleading for help from a nobody. This novel inspired a reflection upon African countries and what hindered their advances: corruption. Expressed in multiple instances of the novel, power and authority in the hands of the wicked is a recipe for disruption.

Fatoumatta: This shit-encrusted tale of corruption and despair belongs to a tradition of postcolonial African literature that is unflinchingly critical of national politics. Hope was abating, disillusionment with Independence was beginning to take hold, and people were resigning themselves to the sad realities of poverty and inequality. In Ghana, the period in question in the 1960s.

Ayi Kwei Armah set out to take a stand and make a political statement, evident in every part of the book. Many similes, hyperboles, painful descriptions, and lots of pontification. It is annoying and makes the book painful to read, but it also gets his point across.

He wrote this book in 1968, 11 years after Ghana’s Independence, when the joy of freedom had given way to hopelessness and corruption was running amok. “Our main character is a struggling civil servant, earning wages too low to allow for a good quality of life. But he refuses to join in the corruption-free-for-all”.

It seems everyone hates him for that. The people who offer him bribes are offended when he refuses to take them, telling him he thinks he is better than everyone else. He is unwilling to falsify documents to get some money. Hence, his wife resents him because if he would only stop acting like he was better than everyone else, they would have enough money not to live hand-to-mouth.

“You have not done what everybody else is doing,” said the naked man, “and that is one of the crimes in this world.”

What kept me reading was how well Ayi Kwei Armah managed to capture the situation in Ghana: corruption, greed, and theft among the leaders, and a sense of utter hopelessness among the struggling masses. It has not changed. Over 70% of Ghanaians still live on less than $2 a day. Corruption has become ingrained into the very fabric of society. In Ghana, doing the right thing is so hard that it is easier to do the wrong something – take the bribe or offer the bribe because going through the correct procedures will not get you anywhere. Moreover, when a person tries to do the right thing, people look at you as if you think you are better than everyone else. So doing the right thing gets you nowhere, whereas doing as everyone is will get you everywhere.

“Corruption is the national game;” “many had tried the rotten ways and found them filled with the sweetness of life,” he writes, and he is right.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Nevertheless, a few passages stood out because even though this book was written in 1968, many of the same stuff happened 60-odd years later.

There is a scene where he waxes on about how after people fought for Independence, they still tried to “act white,” if you will. They pretended only foods and goods from Europe were worth having; they disdained anything ‘local’; they took on English names or Anglicized their names or changed them entirely, just so long as it was something European and not local. Forty years later, it is still valid. When I was growing up, I ALWAYS got offended stares when people asked my name, and I told them. They would say, “No, not your ‘house’ name; I want your real name, your English name.” And then got even more puzzled when I told them I did not have an English name, just my ‘local’ name. Only in the last decade has the tide slowly begun to turn. People have started not giving English names to their children. It has become fashionable to have a Ghanaian name that is your only name. However, unfortunately, forty years and not much has changed.

I almost fell out of my seat when I read this passage in the book. Here, the man is talking to his wife, who has bought out the hot comb and is straightening her hair:

“That must be very painful.”

“Of course it is painful. I’ just trying to straighten it out a bit now, to make it presentable.”

“What is wrong with it natural?”

“Only bush women wear their hair natural” [being called ‘bush’ in Gh is NOT a compliment]

“I wish you were a bush woman then.”

Fatoumatta: This is the book major. Ayi Kwei Armah was espousing natural hair in 1968? However, 60-odd years later, things are only beginning to change. It is slightly more acceptable to walk around with natural hair in Ghana today than decades ago. Moreover, you must be careful because it is looked upon as ‘bush.’

One last thing. It was nice to read. Ayi Kwei Armah has a particular fondness for scatological images that mesh well with his chosen message. I do not doubt that years from now, my enduring memories of this novel will be of the nauseating stench of garbage, the wet slime of fresh vomit, and the numerous images of human excrement caked onto latrines and railings and faces. Witness the following description of a Party man, corrupt by definition:

“His mouth had the rich stench of rotten menstrual blood. […] Koomson’s insides gave a growl longer than usual, an inner fart of personal, corrupt thunder which in its fullness sounded as if it had rolled down all the way from the eating throat thundering through the belly and the guts, to end in further silent pollution of the air already sick with flatulent fear.”

Alternatively, how about this half-hearted attempt to absolve those impelled toward corruption:

“Sometimes it is understandable that people spit so much, when all around decaying things push inward and mix all the body’s juices with the taste of rot. Sometimes it is understandable, the doomed attempt to purify the self by adding to the disease outside.”

Fatoumatta: The novel breaks out of the plot and swings into essay mode when discoursing the topic of politics. The effect is not as jarring as it sounds since politics seem to pervade every aspect of daily life, from the pressures of family members to take the only known route out of poverty to speeches given by rising Ghanaian idealists who grow into fat politicians speaking in ridiculous fake-British accents. The main character is a nameless railway clerk, “the man” throughout, standing in for every poor laborer not eating out of the government’s coffers. Time stretches. The monotony of a single day is drawn onward indefinitely into the bleak and unchanging future. Coups mean nothing when each regime is as heartless as the last, an unbroken string of greedy eyes thinking through their stomachs. Is there any remedy for the disease afflicts the nation, any hope for the next generation of Ghanaians? Perhaps, the road will be long and torturous for The Beautiful Ones Are Not Yet Born.

A book with people just like me, with peculiar turns of phrases I know about, some of my Ghanian friends and classmates’ names I am familiar with and recognized with whom I will keep remembering them: Adoley, Kofi, Oyo, Ayivi, Maanen. I rarely come across fiction that reflects something familiar to me. I forget the power of recognizing oneself/one’s cultural identity in literature. Not many African authors write anything that is not political/literary fiction. Very few write romance of any kind, and very few write a fantasy. So I do not see myself much in the books I read. So it was refreshing to have that change this time around, even though the subject matter was not very palatable.

All in all, I can honestly see why this book is considered classic and essential African literature. You can feel the weight of its literary merit as you read it. It is a critical work that deals with central themes of African corruption, identity, personal integrity, disillusionment, hopelessness, accountability, and African leadership. He wrote it in 1968, and almost everything he wrote about, almost everything he supported/opposed, can see in the fabric of Ghanaian/African society today. It was an important work then, and it is just as important, just as valid a work now.

It left me with many foods for thought and a new respect for Ayi Kwei Armah. However, damn, if reading this book is not like reading One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich: A Novel: you know it is an important work dealing with important themes, but it is sheer torture to get through.

Fatoumatta: The book conveys the profound tedium and despair of ever getting ahead in an honest manner or getting a government that is not just a new corrupt version of the old corrupt government. There is a lot of imagery of shit in this regard, in a simultaneously graphic and abstract style. There are also passages of beauty that describe the sea and even the dignity and inherent order of the man’s railroad job. Finally, a mid-novel interlude with a revolutionary philosopher who has assessed the situation and entirely withdrawn from the confrontation, but not from his beliefs. He serves as the protagonist’s mentor and life vest. For some, this might be too blatant a way to inject the politics, but in retrospect, it worked as a counterpoint to the cycle of coups that change nothing.

Armah’s novel twisted my stomach in empathy with its protagonist. Vivid descriptions and harshly poetic reflections made it an excellent read. Ask me about a writer who is unflinching in his emasculation of an African postcolonial way of life stunted by its mire in corruption and deceit, and I will point to Ayi Armah.

Why do we waste so much time with sorrow and pity for ourselves?…not so long ago, we were helpless messes of soft flesh and unformed bone squeezing through bursting mother holes, trailing dung, and exhausted blood. We could not ask then why we needed to grow. So why should we shake our heads and wonder bitterly why there are children together with the old and why time does not stop when we have come to stations where we would like to rest? It is so like a child to wish all movement to cease.

In harsh words, this intrepid narrator speaks of poverty and despair within a small African village. I have never come across a novel where despair is embodied through such disparaging scenes. Hopelessness is incarnate in our narrator: the man. Yes, the man has no name, but he has a story. A story of immense loneliness and desperation, for he is the only one who desires a simple life of earned income. Everyone around him wants to smuggle goods and bribe for treasures.

A world where the rich want to get richer and the poor–well, the poor like life beyond outdoor latrines, long, non-airconditioned bus rides, and one-room houses:

Everyone said there was something miserable, something unspeakably dishonest about a man who refused to take and to give what everyone around was busy taking and giving: something unnatural, something fierce, something that was criminal, for who but a criminal could ever be left with such a feeling of loneliness?

Fatoumatta: To be the odd one out–what a state to find oneself. With all my heart, I recommend this one, especially for Gambians, especially for Africans, but be prepared to take at the very least six weeks to read a mere 192 pages; be ready to be tortured by sheer boredom for a good part of it; be prepared to read pages and pages of soliloquy whose only goal is to pontificate. Be prepared not to be able to read more than two or three pages every few days. This book is painful to get through; however, it is worth reading it!