By Kebeli Demba Nyima, Atlanta, GA

The British Army, it is said, once taught its officers that courage begins in the mind. It is not the absence of fear, but the mastery of it. In the old regiments of the Crown, valour was expected to be quiet, firm, and without flourish. A commissioned officer was not permitted the luxury of theatricality. He was trained to lead with calm under fire and, if necessary, to perish with restraint. The officers of the King did not publish memoirs about battles they avoided. They wrote letters home in spare language, sometimes with trembling hands, and often never returned.

Heroism in such circles was not declared. It was observed. In the classical world, it was Achilles who faced death knowingly, not boastfully. In Rome, it was Scaevola who placed his hand in fire to prove his resolve. In 1944, it was General James Gavin who jumped into Normandy with his men, not above them. One does not need to invent tales when action writes its own record. In every true army, heroism is modest because its price is steep. Commissioned officers were expected to live as examples and, when necessary, die as reminders. They were held in reverence not for their stories, but for their silent deeds.

Walk past the Admiralty or down Horse Guards Parade, and one is reminded of a time when rank was accompanied by restraint, and rhetoric was forged in the crucible of learning. An officer of the Crown was expected to read Livy, write plainly, and perish without complaint. Ministers drafted dispatches in prose worthy of Addison. Civil servants addressed policy with the clarity of Bagehot. Even the rogues of Westminster such as Fox, Palmerston and Disraeli masked their ambition with wit and intellect. Their successors today offer nothing but the echo of their own mediocrity.

What we confront now is not the soldier-scholar of old. It is the self-mythologising relic of a forgotten skirmish. The retired uniform, the honorary title, the recycled anecdote, these are deployed as substitutes for substance. The result is not statesmanship but theatre, and not even good theatre at that. Their metaphors are stale, their grammar battered, and their confidence unshaken by their own incoherence.

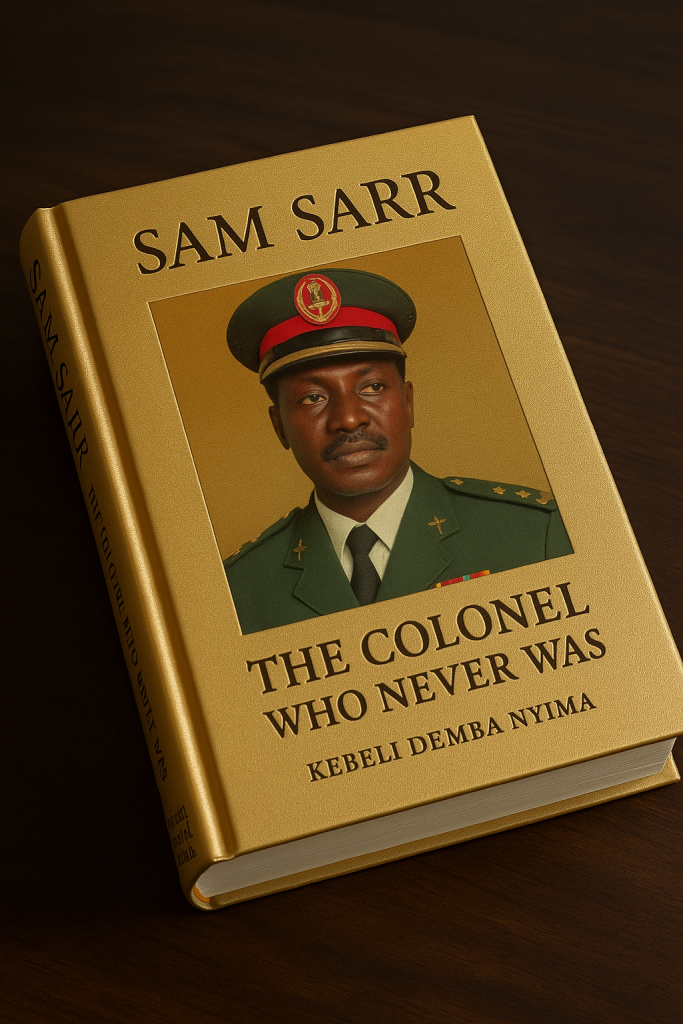

And so, with weary inevitability, we arrive at Colonel Samsudeen Sarr.

He begins, as all wounded egos must, not with argument but with identity. The tone is one of a man who, having mistaken his résumé for a refutation, assumes that listing training locations such as Taiwan, Ghana, and Georgia in rapid succession might pass for a defence of integrity. The Colonel insists he studied under British military supervision, Major Ken Wright, no less. Well then, is this meant to terrify us into submission? We are told that he did not ascend “through deception or political patronage.” Nobody suggested he did, only that he remained intellectually stationary once he got there.

From here, the descent is swift. The Colonel accuses his critic of cowardice for writing under a pseudonym, as if truth requires an ID card. But Plato’s Apology survives not because Socrates showed his passport, but because he had something to say. The name “Kebeli Demba Nyima” may or may not belong to a man of flesh and blood. What concerns us is the quality of thought, not the postal address.

And since the Colonel seems unmoved by philosophy, let us speak his native tongue, British tradition. What of George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair? What of George Eliot, born Mary Ann Evans? What of Lewis Carroll, born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson? These were not anonymous cowards but towering intellects who understood that ideas are often clearer when detached from personality. A pen name is not concealment. It is distillation. Writers do not always seek the glare of recognition. Some prefer precision over persona, clarity over credit. Not every author is grasping for applause in the town square.

To demand a name is to admit that the argument cannot be addressed. It is an attempt to flatten critique into gossip and to confuse identity with authority. But ideas are not passports. They are not validated by the biometric stamp of the state. They must stand or fall on their own merit. If Mr. Sarr cannot distinguish between an author and a brand, that is his problem, not literature’s.

Then comes the trembling sword of his defence, FERPA laws. He assures us that American college records cannot be accessed online, a stunning discovery, but one that does not explain why Dekalb College itself cannot find him. If he is indeed a graduate, one wonders why his name does not echo in their halls, or at least appear in the margin of a yearbook. He has answered a factual challenge with bureaucratic fog and hoped we would mistake it for thunder.

Audit trails reveal what Sarr carefully avoids saying aloud. Dekalb College is, and always has been, a two-year community college offering only associate degrees. That is the academic pedestal upon which he plants his flag and from which he sneers at scholars with doctorates, fellowships, publications, and peer-reviewed output. One cannot help but marvel at the absurdity. Can a man who lists an associate degree as the apex of his intellectual development seriously claim to speak on equal footing with those who have spent decades in archives, laboratories, and lectures?

Unless Sam Sarr has been conferred some invisible doctorate by divine memo, he is not a peer among thinkers. He is, at best, a footnote in the file of unqualified men made loud by national amnesia. There is no shame in an associate degree. There is, however, an unmistakable embarrassment in pretending it is something more, particularly when used as a sword against those who have actually earned what he mimics.

The tragedy is not that Sarr has so little to show for his time abroad. The tragedy is that he imagines it is enough. That two years of entry-level study, unverified and unremarkable, somehow entitles him to pontificate, to belittle, and to question the legitimacy of those who have done the work he never attempted. His delusion is not academic. It is moral.

And so to the origin myth. Colonel Sarr has spent the better part of his public life confusing performance for valour, and proximity to danger for participation in it. He likes to speak, indeed, he cannot help speaking, of his military pedigree. But let us speak plainly. Colonel Sarr has never seen combat. Not once. He has never discharged a weapon in the defence of country, of peace, or of principle, unless, of course, one includes the bullet he lodged into his own leg.

Yes, that tale must now be told. In 1992, when the Gambian contingent was preparing to join the ECOMOG peacekeeping force in Liberia, where young men were dying in the thousands for West Africa’s fragile stability, Colonel Sarr, then a senior officer, was selected. And what did this so-called soldier do? He shot himself. A self-inflicted wound passed off as an “accidental discharge.” A coward’s passport home disguised as misfire. Imagine the spectacle, a commander who engineered his own evacuation before the mission began. In classical Sparta, he would have been stripped of arms and exiled. In ancient Rome, condemned for desertion. In Wellington’s army, court-martialled without hesitation.

Military historians speak of cowardice before the enemy as the most unforgivable sin of command. Consider Lt. Col. Henry Blake of the Royal Fusiliers who, during the siege of Lucknow, refused to abandon his men under fire. Or General Marcel Bigeard of France, parachuting into Dien Bien Phu knowing he would likely be captured. These were officers who knew that courage must be shown, not spoken. Sarr, by contrast, absented himself from the battlefield with a gesture so ignoble it would make even the politest war college wince.

But the story does not end with the gunshot. It merely begins.

After a brief stint in Mile 2, The Gambia’s most infamous prison and a place whose darkness many endured with dignity, Sarr did what many suspected he would. He begged his way back into the arms of the regime that jailed him. Not through resistance. Not through reform. But through surrender. During one of Yahya Jammeh’s diplomatic appearances in New York, Sarr orchestrated a meeting with “the Big Man.” Over lobster, yes, lobster, he recanted his earlier criticisms, denounced his own writing, and pledged renewed allegiance. It was less a reconciliation than a culinary conversion.

From that day forward, he was no longer Colonel Sarr. He was Sam Lobster.

This tale is not urban legend. The confession lives in the archives of Freedom Newspaper, captured by the late Pa Nderry Mbai, whose astonishment was exceeded only by his accuracy. Those who wish to verify it may do so, unless, of course, they fear facts as much as Sarr fears self-reflection.

And what of the years abroad?

While many Gambians in the diaspora used exile to build skills, educate themselves, or organise political resistance, Sarr passed through America like a tourist in his own biography. Two decades in the United States, and not a single degree to his name. Not even a specialised trade. He returned home armed only with anecdotes and grievances, convinced that volume could substitute for value.

He now claims to have published three books. But publishing is not writing, and writing is not thinking. These works are neither scholarship nor literature. They are laundry lists of self-praise, bound together by poor editing and feverish repetition. They quote no one but the author. They argue with no one but shadows. One reads them not for illumination but for pathology.

I, for one, do not advertise my credentials in every sentence. I edit for people whose names will outlive mine. I illustrate manuscripts whose footnotes matter more than their titles. I review books for what they say, not who wrote them. I do not write to remind the world of who I am. I write so that others may remember what reason sounds like.

The difference, Colonel, is that I have nothing to prove. You, it seems, have nothing else.

In truth, Colonel Sarr has never been a soldier in the Platonic sense, never a writer in the Orwellian sense, and never a public servant in the Burkean sense. He is a poseur of the highest order, a man who fled duty, then returned to narrate it as legend. His only consistent trait is an allergy to honest self-examination. He demands academic credentials from his critics, but refuses to present his own. He challenges others to reveal their names, but cannot reveal the content of a single original thought. He calls for transparency, while hiding behind a curtain of pomp, pension, and paragraph-long self-adulation.

If justice were to prevail, the Gambian Armed Forces, as a professional institution accountable to constitutional order and ethical service, would retroactively review his career record and recommend the revocation of his honorary rank. Had Colonel Sarr still been in uniform, his actions including fabrication of combat narratives, undermining of institutional dignity, and public misrepresentation of training would fall squarely under Section 57 of the Gambian Armed Forces Act, which governs conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline. At minimum, such behaviour warrants summary demotion, and in some jurisdictions, including Commonwealth doctrine, would carry the additional sanction of censure by court martial for conduct unbecoming of an officer.

Even in retirement, military titles are not private ornaments. They are public trusts. They imply honour, service, and sacrifice. To weaponise that trust in memoir and media, long after avoiding the obligations that come with it, is not merely dishonourable. It is parasitic. Sarr has feasted on the institution he never fed, and now cloaks himself in credentials no serious army would tolerate from a second lieutenant, much less a colonel.

Literature teaches us to separate myth from memory. Homer sang of heroes who bore wounds for others. Orwell wrote plainly so that lies could not pass unnoticed. Burke believed public service must be grounded in humility, not self-congratulation. Sarr belongs in none of these traditions. His is the tradition of the deceiver unmasked, the hollow man made loud by the silence of others, the footnote inflated into a fable.

Let this not be the last word on Sarr, but the first word in a broader reckoning. The Gambia cannot build a serious republic if it continues to elevate ceremonial actors over civic contributors. If the country is ever to mature politically, ethically, and intellectually, it must learn to name its false prophets and strip their borrowed garments. That begins with Sarr.

He paraded when others bled. He published when others studied. He spoke when others served. And now he demands that we remember him as something he never was.

No.

Let us remember what he ran from, and never confuse it with what he later tried to write.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of any institution, organisation, or publication platform with which he may be affiliated. The author accepts full responsibility for all interpretations, claims, and analyses presented herein.